My Tagore

Alokeranjan Dasgupta

(Keynote address delivered at the Tagore Symposium at Darmstadt on the occasion of the Indian Festival in Germany, 1993.)  |

Pencil sketch of Tagore, by Amitabha Sen

When my friend Lothar Lutze urged me to soliloquise on my Tagore, the immediate reflex that circled in my mind was to reverse the sequence of such an undertaking and dwell simply on Tagore's Me. For one thing, here is a man who tends to mould the very design of my

Dasein, the niche of my innermost being and becoming. There is here a sort of pre-ordained determinism at work. It has often occurred to me, whilest pondering on my behaviourial responses to certain phenomenal stimuli, that it is Rabindranath Tagore's characteristic way of confronting reality that has invariably affected mine. It has struck me with a kind of shudder in those junctures of time that he, in an all-encompassing manner has been integrating, if not devouring, my biography. Someone who does not know Tagore could call this a kind of impinging on Tagore's part, in view of the fact that although he composed a few autobiographical fragments, he never took this form really seriously in the context of Art, for he maintained that a true poem transcends its materials and aptly compared a poem to 'A dewdrop which is a perfect integrity that has no filial memory of its parentage'. Tagore's lingering distrust of the relevance of biographical details to any of his works could suffice to set the scene today here in Darmstadt, where 72 years ago, paradoxically, his legendary personality shone so luminously that his Art was totally lost sight of. Like many of the citizens of Darmstadt who were mesmerized during the

Tagore-Woche 1921, I myself, in Bengal, also became vulnerable to the legend called Tagore in my childhood days at his

Ashram, Santiniketan, and possibly considered his creative works rather secondary. Recently while reading Holger Pausch's

Biographia Literaria of Paul Celan, a writer who, as a poet in and of exile, has loomed far larger in my life than Rabindranath Tagore, I chanced upon the author's laconic remark:

Biografisches, Sekundares. Apparently, this condescension towards the biographical as something secondary bears some resemblance to Tagore's view-point. But while reading between the lines I found the author was doing this because most of the facts concerning Paul Celan's life are irretrievably lost and therefore he was inviting us to concentrate solely on his poetry, which reads like hieroglyphics. Not so with Goethe and Tagore. Almanacs such as

With Goethe throughout the year are revised every now and then to record each moment of his illustrious life. Similarly, hundreds of bibliographic documentations on Tagore are now and again rushed into print so that we are bound to learn by heart every item about his life. In itself, this is no heinous crime. But something is deliberately mistaken here. Quite a lot of sublimising and stylising ingredients are concocted to project him as greater than he was. Long ago Keats has taught us that greatness as such has nothing to do with poetry. But Bengali Tagore-biographers have always irritated me in their painstaking mission to glorify the otherwise great man with overhead projections in order to minimise the greatness of his poetry.

|

A scene from Tagore's funeral procession.

The Tagore euphoria, European or otherwise, has been aptly branded as 'Idolatrous' and 'Bardolatry' by Stephan Zweig and William Radice respectively. As a child I felt an easy prey to this kind of prismatic reception. As a boy of eight I caught glimpses of the mammoth mourning procession escorting Tagore's dead body from our south Calcutta flat, bitterly wept and felt obliged to register my elegiac reaction in a fragment of verse. The next morning I was put to shame when I saw that in most of the Bengali newspapers the funeral procession was depicted in flowing diction. I tore up my prosaic composition describing the death of a poet. That was 1941, the year when Rabindranath Tagore, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf passed away. Later on the other two names came to mean much to me and it was in an act of devotion to their geniuses that I dismissed the celestial hierarchy which gave Tagore a higher rank than the two others. But in those early days such an act would have been regarded as the worst possible sacrilege. In one sense I was lucky not to have experienced Tagore alive. For then I might have become completely immersed in him, bereft of all the contours of my own self, however small its dimension may be in relation to Tagore's. It was 1944 when I went first to Santiniketan and got immediately as a pupil of Pathabhavan to class 6, without any rigid selection test. This liberalism was absolutely in keeping with Rabindranath's educational principles, those of opening doors for young souls to give them a chance to explore themselves amid natural surroundings without the censorship of examination. The very first text which was taught to us by our teacher of history stemmed of course from Tagore. This had the impact of an incantation on us. It starts like this: 'Man is unbridled. When he lived in the forests, there existed between him and Nature a harmonious correspondence. But as he grew into a city-dweller, he lost every feeling for the forest. This man chopped the tree which once offered him divine hospitality, just in order to build his city house with wood and brick... And now the forest is no more. A calamity lies before us. And this is not specifically an Inidan problem. Everywhere in the world it has become immensely onerous to guard the property of the forests from human greed. In the United States of America wide forests have been eroded. Sandstorms are encroaching and burying vast acres after damaging them ...'

|

Indira Devi and Tagore, 1886.

Aged eleven or so, we were spellbound by the charm of Bengali prose and did not comprehend that we were taking our first lessons in Ecology, an issue which has now become so inescapably present and pressing. The very first evening we were taken to a Grand Dame called Indira Devi Chaowdhurani to be initiated into Rabindrasangit, i.e. songs composed by Tagore. Indira was the niece of Tagore, and known to be a key-person in unlocking the secret recesses of Tagore's soul. Can it be no more than a sheer coincidence that she sang

amar parano loye which Tagore sang in Darmstadt in 1921? It is a strange proposition that a Tagore song can be translated from Bengali even into Bengali. I would not wish to attempt anything of that kind. If somehow the import of the refrain referred to can be paraphrased it might be: 'What play would you play, the beloved of my life, with my life?' Since the very first time of my responding to this message, I must confide here in all humility that I have not been able as yet to refrain from this refrain. There came about at that moment the beginning of a tryst with my destiny which endures today. For since then Tagore seems to me to be a kind of decisive, albeit deceitful, deity wreaking havoc on me, on my own poetic intention. In one of the first hours of initiation into Sanskrit, Nityananda Vinod Goswami, our ever absent-minded teacher, taught us the etymology of the term

bhakti, a word which has now acquired an enormous momentum in Germany. He reiterated that

bhakti does not imply a mindless submission of the devotee to the deity -- what it really means is the splitting up of the one in two components and that it is the playful dialectic between the two entities that really counts in

bhakti. Later on I came to know that this duality in love or reverence has its correspondence in the European epithalamium mysticism of St. John of the Cross. But at that time I was not acquainted with it and found it convenient to surrender my will to Tagore in a spirit of total submission. A distinction between the East and the West did not exist for me. The motto of the Visva-Bharati Ashram where I happened to find myself, was:

Where the world becomes one single nest. This vision of the world being visible there, I felt like a caged bird released in an asylum which was called

Ashram. I could choose my selfstyled flight again. But I found myself captivated by this freedom. In German there is a wonderful word. Spielraum, which means, a space to play in. I had this playing space and yet I must confess that I was not in a position to make my own choice. The atmosphere of the

Ashram was profoundly embalmed with the fresh memories of Tagore. Even his recent death looked tantalizing, intriguing and yet invoking us to be in utter unison with the all-embracing and all-embarassing spirit of Tagore. As a result I yielded myself, I played into the hands of his hermetic texts and had quite often an afflicted conscience when I could not cope with them, empirically speaking. I felt miserable when I thought a thought which did not chime in with Tagore's articulation. He became my judge in the

Old Testament sense of the word, who might annihilate me all of a sudden, should I deviate from his solely valid ordering of all things. Attuning one's life force in a specific manner: this was the ambience of Santiniketan. And this meant a lot to me. Looking back I concede that I learned something thereby which hitherto has remained a sort of guideline to me. The Bengali word for my feeling then is

Vani, which denotes 'a message', but connotes a 'text with multiple texture'. It was at such a meaningful conjunction that mahatma Gandhi, who took over the charge of Santiniketan after Tagore's demise, came to Santiniketan. It was his very last sojourn to be in this

ashram, a place far more complicated than his own linear one in Sabarmati, before he was shot down by a Hindu fanatic. This 'half-naked Gujarati Saint', while playing with us, told us one afternoon in pure Bengali:'

amar jiban-i amar vani', meaning, 'my life is my text or message.' I felt quite frisky and frivolously retorted: 'Actually speaking, Tagore's word is, essentially, my life.' Gandhiji, however, invariably missed the entire point. He went on to demand from us for his own

ashram five rupees against each autograph. This I turned down on behalf of my fellow students, without even consulting them. In staging such a protest, I simply clung to Tagore, who believed following Biblical authority: 'In the beginning there was the word'. It was, I thought, a kind of poetic justice which I served to Gandhiji. In fact I felt rather proud, having done it. Even today I am convinced that for Tagore words, spoken or written, were of the utmost significance, out of which life emerges. It was at this point that I took to Marxism. A Marxist Guru came from Calcutta to Santiniketan and we were ready to be converted. Amartya Kumar Sen, now an economist with a worldwide reputation, and Tan-Lee, a Chinese classmate, who never dreamt of turning into a Maoist, assisted me in this iconoclastic process. The Communist Party of India at this time was about to go underground and we three youngsters took extreme pleasure in circulating its inflammatory leaflets, which were directed to the mill-workers of Bolpur and against the recently gained Independence of India. We sought hide-outs for our adventures in the adjacent villages lurking in the district of Birbhum. My favourite poet became Mayakovsky, and not Rabindranath Tagore. Here were the first beginnings of the process of de-Tagorizing myself. I did not consider myself any longer as a product or by-product of Santiniketan. The embarassing discovery was however that while I tried my utmost to turn aside from the establishment called Tagore, almost all the senior Bengali poets of the thirties, who had earlier attempted to define their own solipsistic modernity by denigrating Tagore, returned to anchor themselves in him. Their precipitated return to the moorings of the old bard somehow convinced me that I should stay on at Santiniketan awhile, albeit reluctantly. It was at this stage that I entered the allegorical world of Tagore's dramas. There was an element of irony in this. We were already hostile to the webs of ritualization tending to start in Santiniketan and we already called it

Achalayatan (the outdated hermitage) after the poet's drama of the title, composed during the

Gitanjali period. One day, Hirendranath Datta, our English teacher, who fell into evil repute for having translated

Lady Chatterly's Lover, wanted to stage this drama. Subhadra, a minor character of

Achalayatan, an innocent rebel in his teens, is forced by the Ashramites to enter a long period of penance and repentance for having flung open the forbidden northern window, beyond which the outside world existed. There was no one available to play this part among my friends as none was ready to repent for a crime which was no crime. I volunteered, but at the rehearsals miserably failed to cry at the climactic stage. I learned my text like a clock-work doll with a precision that annoyed Hirendra. He even persuaded me to drop a phrase here or there and begged me to express my grief by producing spontaneous tears. I managed doing it at the final performance, and I still remember with nostalgia, how Hirendra, at the interval, congratulated and hugged me and I was still weeping bitterly. I hate anecdotes and yet I feel that this example substantiates the aspect of cathartic release in Tagore's dramas. Accidentally I obtained a copy of Edward Thompson's study of Tagore from the latter's ex-secretary which contained the poet's marginal comments. Thompson's comments [that??] 'Tagore's plays are vehicles of ideas and not of action' drew a reaction from the author himself as follows: 'what a stupid example of tilting at windmills!' Now I am convinced that Tagore's remarks are fully justified. The Peoples' Little Theatre's wonderful productions of

Achalayatan and

Kaler Jatra (The journey of Time), the latter written after the poet's visit to Russia, were action-studded without evoking the impression that these stemmed from the pen of a poet for whom words meant almost everything. On the other hand Bahurupi's production of

Raktakarabi, a symbolical drama aimed at the vices of Capitalism and totalitarianism, amply show that Tagore's words, properly

|

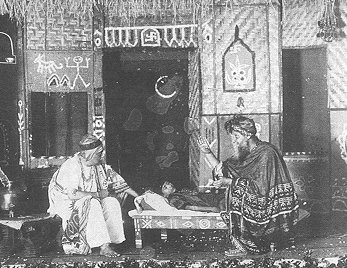

Tagore (right) as Fakir in his play Dakghar, 1917.

understood, unleash teeming action and movement. The problem arises when the poet-cum playwright shifts from the hermetic to the hermeneutic and by overexplanation mars the zone between what is spoken and what is performed. It is the task of today's theatre director to trim those passages mercilessly so that the suggestive power of the intent comes out. I am very happy that Mehring in his Calcutta production of

Dakghar removed even the powerful one line utterance: 'stop your prattle unbeliever, don't you utter another word.' which was spoken by grandfather with a waggling index-finger. Explicatory utterances like this have made Maurice Maeterlinck, who got the Nobel prize one year before Tagore, a non-entity in today's theatre. Critics who bracket them together forget that Tagore suggested several alternative ways for his procedures to bring out their own Tagore. Now it seems to me that Tagore apprehended the inclinations of his future procedures and hence created several versions of most of his dramas with unlimited freedom of interpretation in prospect. If Tagore, like W. B. Yeats, entered upon the stage and intervened in the performances of the dramatis personae, he did not do it in the manner of

deus ex machina, but in the spirit of involvement. That is why, although at times his intermittent presence in his drama calls up the image of the head of a joint family, one can identify oneself with his characters, evil and eternal alike. Tagore demands from us this effort at identification. And he succeeds in this by the songs in his dramas, using them, rather than hands, as he says, to hold the door ajar. These songs serve two purposes in his dramas. First, they work like philosophically reinforced lifebuoys in the course of the voyage through characters, offering a helping cue, when speech or action both become superfluous. Secondly, they create a relieving space in the complex density of human experience. They help the characters to launch out on a mysterious voyage, implying that a human being is not a mere prisoner of causality in the time-space continuum. Identifying one's situation and leaving it behind -- these are the two functions of Tagore's songs. After fulfilling these two needs these songs descend from the stage and become incorporated in the life of a Bengali. Tagore's claim that if his creative enterprises at other genres do not survive, his songs will remain for posterity does not seem to me exaggerated. For through these songs he becomes the most intimate spokesman of Bengalis in all walks of life. If there is the beginning of the gathering of monsoon clouds, they will not chant according to the

Miya ki mallar of the classical

Raga-music, but resort to the

Rabindrik song-sequences where the poet applies mixed variation of this musical mode. A leading poet of my generation,

Sankha Ghosh, though no believer in God, would, on the demise of a dear friend, turn for solace to the three-fold pattern of totality expressed in

Rabindrasangit, consisting of

Prakriti (Nature),

Puja (Worship) and

Prem (Love) and recite those songs as poems. Rilke, too, was pleased to read

Die Lieder des Inders, i.e. the songs written by the Indian. He ignored the fact that these were also composed by the poet himself. At this point I cannot help reflecting that when Heine wrote some 350 Lieder, they remained incomplete till a Schumann or a Silcher set them to music, whereas Rabindranath Tagore, the most diligent translator of Heine into the Bengali language, both wrote and composed the music of at least 2500 songs. Bengalis are never tired of ambling through the multitudinous chambers in the spacious edifice of Tagore's music, but thereby often fail to notice the intrinsic art of these songs. They express all their moods and thereby promote a special kind of nurtured aphasia. The songs synchronise their silence adequately, furthermore, they heal people's affliction or agonies. This therapeutic use of Rabindra-songs has undoubtedly vulgarized them to some degree. Their currency has somewhat debased their nonutilitarian status. What I now try to do, therefore, is to receive these songs beyond therapy with a sense of Brechtian detachment and alienation. The question may be asked: might one not treat these texts as an integral segment of

Gesamtkunstwerk, total art-work, as Wagner should have put it? Did not the poet integrate them in his opera and dance drama as in his fiction, contextually and organically? To extricate them from this totality for private or collective use would invariably mean a kind of tampering with his testament and so create a monopolizing vendetta of vested interests to lobby upon. Exactly this is due to happen now that the Bengali culture has been geo-politically divided. One example will suffice here. Tagore, while looking after the ancestral estate at Selaidaha (now in Bangladesh) came into close contact with the common village folk and as a result could write a considerable number of excellent short stories. Tagore's birthday celebration, ceremonially held with great pomp at Selaidaha, in May 1990, gave rise to much controversy where a final statement was issued as follows: 'The poet's stay at Selaidaha yielded a rich harvest of short stories. The atmosphere here had inspired him to be a prolific writer and as many as fifty-seven stories were written while he stayed here. As soon as he shifted to the arid undulating plains of Birbhum (West Bengal) his creativity ebbed ...' (

The Statesman Weekly, 19.05.90). How accurate yet lop-sided a view this is! On my permanent return to Calcutta from Santiniketan in 1949 I felt fortunate in being able to establish a topographical distance between Selaidaha and Santiniketan. In other words, I was perilously poised between the two centres of Tagore's creative activity and, while falling in love with the women characters of those short stories, could also gauge the dimension of complexity of the urban figures which were delineated by Tagore during his sojourn in Calcutta, the third seat of his creative vitality. It was here that Tagore broke away from time-honoured norms and ushered in the ever-unsettled 20th century. In 1910 human nature changed, observed Virginia Woolf. So did Tagore's, at least in his psychological fiction. Tagore was one of the first Indian readers of Freud's

Interpretation of Dreams in 1915 and in his novel

Chaturanga (1916) created Sachish, a male character, in conformity with the libidinous urges of Freudian psychology. This character could not rest in any one position; while swaying back and forth between rational positivism and devotional Vaishnavism he experiences the following unabashedly erotic dream:

Someone embraced my legs. At first I thought perhaps a wild beast, but beasts have hair -- this does not have them. I thought, something like a snake, a creature I do not know. God knows how is its head, body or tail -- what is its technique of destruction. because it is soft, it is repulsive, that lump of hunger. His female counterpart Damini, too, is no longer the personification of the archetypal perfection, life-affirming principle, as Tagore wanted her to be. This woman wriggles out of the controlling tentacles of her creator, a sentinel of ethos or rectitude in his talks on religion, philosophy and society. She stands in a no-man's land and moves thus away from the Tagorean centre of auspicious gravitation: 'Where there is no reply to any answer or call on such a boundless and pale-white ground, Damini stood like one struck. here everything has been wiped off to reach the primal whiteness. Only a big NO languished near her feet'. Only then we perceive how unqualified Romain Rolland's observation is when he says that: 'Tagore recoiled from everything that stood for NO'. It is in this fallacy of representing Tagore as more of a pronounced normmaker than he was that most of the translations in Europe of Tagore literature have utterly failed. Hence

The Song-Offerings or

Gitanjali, which does not conform to any institutional form of religion, becomes in German

Liedopfer (The sacrifice of songs) or

Weihgabe in

Liedern (Consecration through songs). Hence the Swedish version of the already transplanted

Der Gartner (1913) turns

Ortagardsmastaren (1914) in which the Jesus of Nazareth was, on his resurrection, taken to be a gardener by the women. That is why even the sensitive psyche of Andre Gide surrounds the secular lines of

Gitanjali, i.e. 'Dwelling in my haunted ears / you want to enjoy your own song', with a

Parvis, which in French connotes the outer sanctuary of a cathedral. A translation should be a challenge to re-experience cultural matrices of the original where the author constantly oscillates between his monistic resources and multiple beings. This was exactly what occurred in the very last decade of Tagore's poetry where the author transgresses his own world view and becomes another in the mode of Phoebus-Apollo, the deity of poetic creation, who is gathering 'raw materials from somewhere beyond the conscious mind'. For myself too, as a Bengali, it has never been easy to grasp this disposition: this desire of the poet to leave his own established nexus and penetrate 'The uncollected voice of the collective unconscious'. While preparing the anthology

Der andere Tagore (The other Tagore) I was happy to have Lothar Lutze select the poems from the poet that are enigmatically caught between the one and the other. I was responsible for the Tagore, the immutable one, who would never give in and try to remain in unison with his balanced universe whereas Lothar Lutze, the other and the detached translator, preferred the alter-Tagore, who was subconsciously drifting away from his pre-ordained personality. It was in this tussle that we both came to discover the greatness of Tagore which was otherworldly and profane alike. Alex Aronson, whom we miss here, scanned these two aspects when he specifically noticed in our translation the juxtaposition of the worlds similarly to those of Hoelderlin and Paul Celan and added that this range of variety was inherent in the style of Tagore and not an outcome of whimsical interpolations by the translators. It is essential for me now to distil the quintessential substance of Tagore from within vast continent of creations produced by one of the most prolific writers of the world. In doing so, I prefer the writings where he releases his creativity from the well derived categories of his conceptual persona. Not that I disregard his tracts and treatises on religious, political, philosophical and educational issues. In fact I learn much from them and find them profoundly relevant in our confused post-Gulf war world. But I derive much more pleasure when, by opting for mortality, he rids himself of his inaccessible attributes and plays. Both these selves, the instructive and the playful, are organically existing in him. In alternate surges he replaces the one by the other. He himself calls this paradoxically 'the unity of selfcontradiction' in his autobiography entitled

Atmaparichay. If now, accordingly, he becomes an optimistic pathfinder in a discursive prose, in the very next moment he voluntarily loses direction in his book of verse and shakes off all value judgments. It is towards the latter that my sympathy lies today.

|  |

Illustrations by Tagore in Sey

My friends admonish me when I revel in his prose-fantasia

Sey (He), written just four years before his death. I am reminded of Kafka's

Er (He), an exquisitely aphoristic collection and still find Tagore's

Sey more Kafkaesque, in its far more inchoate delving down into the subliminal depths of awareness where 'he' becomes 'she' and yet 'it' and ultimately dissolves the egoistic sublime of the first person. This brings me to Tagore's paintings, which, drawn between 1928 and 1940 amount at least to 2000, and thus compete, so far as numbers are concerned, with his songs. Starting with hesitant calligraphies and doodlings, he swiftly did away with the harmony of ornate symmetry, and, mingling powerful colours evolved a different world replete with rudimentary mixed entities, where an unfathomable darkness prevails. Here desperation becomes doubt, an old man becomes a young woman, a woman an animal. here the poet as a painter risks being unpopular among his devotees who mindlessly adore him as Gurudeva. And here the king of aesthetic values, divests himself of all majestic parapharnalia, and manifests his genius as a fellow-mortal and not as a supernova.

Painter, then musician too, but above all writer-poet, dramatist, controversial essayist: my Tagore, the Tagore I have experienced throughout my life from my volatile youth onwards spanning the widths in genre and theme. A fecund spirit who can move with delicacy and sureness on the height of sensibility, yet plunges readily into the abyss. Neither Saint nor Guru, he partakes nevertheless sufficiently of authority to constitute for me, one who writes in the Bengali language, unalterably an artistic and a human challenge.

Edited by Qwest - 19 years ago