Jodha Akbar 3: Cynicism abounding

Folks,

I loved this episode for the sheer, bare-faced and bare-knuckled cynicism that pervaded it from start to finish. And this was not just at the Jalal-Bairam Khan end, though the best parts were there.

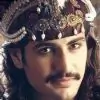

Registan ka gulab: First, there is Jalal, knocking a good seven soldiers flat as usual during his jungi riyaaz (in the brown outfit that we came to know so well), lending half an ear to the babblings of the Jodha ka diwaana. This last was bizarre, for no common sipahi in the Mughal forces would have dared to unload such stuff on the Shahenshah if he valued his sar.

Nor could one readily grasp where this chap got to know about her makhmali twacha & lacheela badan long distance😉, for if he had come close enough to her to make out these mind-blowing attributes, he would have been dead!

Clearly this clumsily worked out interlude was meant to reinforce the Amer ki pukar that will soon take over Jalal's zehen and drive him to take insane risks on his adventure to the heart of Amer.

The expression on Jalal's face as he slowly repeats the name that Abdul has just spoken, Jodhaa... , is amazingly evocative, as is his voice. It is as if he was rolling a particularly delicious sweet on his tongue, savouring the pleasure of things unknown.

And as for the desecration of the temples, this was standard operating procedure for all the invaders of India in those days, and I presume for the Delhi sultanates that followed. So I suppose Jalal hardly thought about the matter at this point, except inasmuch as his concern about the superior jungi kaabiliyat of the Mughal sipahis was concerned.

Let us now skip over the ek aisi prem kahani jo shamsheer ki dhaar par chale, aur payal ki jhankar ko bhulne na de. For one thing, I cannot remember even having heard Jodha's paayal ki jhankar (I would personally prefer noopur dhwani) any point of this tale of ours. 😉

Scheme of last resort: Also over the portly Bharmal's discussion, with his sons and nephew, about how to tackle the danger that now lies at the door of Amer. He is clearly besides himself with fear - the good old khauf-e-Jalal at work - and his plan of action has only one merit, that it is the scheme of last resort.

Seeing the rampant disunity that pervaded among the Rajput royalty, how Bharmal expects that a few marriages with his daughters - and he does not even have enough of them to make an impact, as there are only three!😉- will set things right and produce unity against the Mughals in a miraculous fashion boggles the mind. It is in fact far more likely to lead to more squabbling and drawing of swords about which princes are to be allied to Jodha and her two sisters!

The only merit of this sequence is that it fits in with my theme for this post. Bharmal does not even think of fighting on his own, and is instead focussing on how to get others to pull his chestnuts out of the fire, and he does not hesitate to use his daughters as bargaining chips.

Ek bar kisise uski kamzori ko cheen liya jaye: Of the two scenes that lit up this episode and made me choose this title, this one, between Bairam Khan and a devoted servitor of his, was in fact the more brutally cynical and the more chilling. Kyonki dushman se dimaagi khel khelna to phir bhi laazmi haim, par apnon se nahin.

The fact, however, is that Bairam Khan has no apne besides Jalal and his beloved Salima Begum, and all others, no matter how blind their devotion towards him, are mere pyaade to be manipulated, thru fear and blackmail, used, and then discarded without a second thought.

There is a cold desert in the innermost core of Bairam Khan's being, and he has no ability to care for another as Jalal can care for an Abdul. It is this fundamental difference between their basic natures, coupled with Bairam Khan's increasing tendency to treat Jalal, even in public, as his supine pupil, that led to Jalal's estrangement from the Khan Baba he loved so genuinely.

I was chilled to the core as I watched the poor servitor bring his first born to be blessed by his Aaka, and noted the shocked misery on his face as he listens to his Aaka's implicit threat - Laut kar aana to hamari begum ki kalaayi ka paigham zaroor lana..- and realises the fate that awaits his beloved baby son if ek bhi choodi tooti on the 30 day journey to Agra.

Bairam Khan looks far more maniacal here than Jalal did during the first two episodes, and far more terrifying. Zulm ki inteha ho to aisi. And his faithful pupil watches him, eyes narrowed in concentration as he asks Kya hoga, Khan Baba, agar ek bhi choodi tooti to?

The answer is revealing, and encapsulates Bairam Khan' s whole philosophy of life and of control.

Nahin tootegi, Jalal. Yeh bachcha uski kamzori hai.. Ek bar kisise uski kamzori cheen liya jaye, to phir us aadmi se jo chahe karwa lo...Isi ko dimaagi taaqat kehte hain. Aur yehi khel tumhein khelna hai...

As he continues, adapting the lesson he has just given Jalal to the Rajput context, where unhein nahin, unke guroor ko khatam karna hai.., Jalal's eyes, narrowed in close attention, change their expression. Slowly, the single-minded concentration is replaced by sardonic amusement as the familiar, sneering half smile twists his mouth.

My heart was wrung by this infinitely sad tale of the deliberate betrayal of loyalty and faith, and the expression in the eyes of that baby's father haunted me long after the episode had ended.

Dimaagi taaqat ki hadein: Yes, this is a dimaagi taaqat, but what Bairam Khan does not know, and thus cannot teach his pupil, is that when a man is desperate enough, snatching his kamzori from him might not result in slavish obedience out of fear, but in open and murderous rebellion.

In the end, large bodies of men cannot be subjugated and ruled for long out of fear alone. They need to have a stake in the structure of governance, and this can come only if they feel safe and protected by their rulers. Without such a sense of belonging and security, there is none so dangerous as the man with nothing to lose.

The contrast between Bairam Khan's ruthlessly cynical, and eventually faulty doctrine, and Akbar's single-minded devotion to the welfare of his awaam could not be sharper. Which is why Akbar was Akbar, whereas Bairam Khan was only a footnote to history.

Zindagi ya mohabbat?: The real brilliance of this last scene lay not in what Bairam Khan pontificated on (abandoning, for once, his quick fix of sar kalamofying!) in the end, Isi tarah humein unka sar jukhana hai.. The principle it reinforced was after all the same as in the earlier choodi scene.

The whole creepy segment, of Jalal apparently intending to exercise his droit de seigneur* by seizing that hapless woman, stood out at two levels.

NB: The droit de seigneur, or the right of the feudal lord, refers to the medieval European custom of any pretty bride being sent to spend her wedding night with the feudal lord, an arrangement to which the husband dared not voice any objection,

Firstly, it was a kind of power-point display of acting by Rajat, as he forces the husband, at knife point, to abandon his wife to her fate in order to save his own skin. The eyes look, not angry, not even threatening, but coldly calculating. Their focus is eagle-eyed as Jalal seeks to assess: At which point will this man break? And break he does, as Jalal laughs his mirthless laugh of triumphant certitude, and Bairam Khan applauds him for a lesson well learnt on how to subjugate the Rajput enemy by breaking, not him but his pride.

The bitterness of the soul: But secondly, and far more interesting, it is a cri de coeur ( cry from the supposedly non-existent heart) of Jalal against the very concept of mohabbat, which drives him to exasperated rage. This stands out in his angry words: Gair zaroori mohabbat ki khatir kitna kuch.. Samajh nahin aata ki mohabbat tumhari zindagi par raaj kaise karti hai?...and he kicks the man to the ground in ferocious contempt.

He wants to demean the very idea of mohabbat, whence his sneering comments to the woman as he tells her to go back apne pati ke pas ( not shauhar?), ek aisa insaan jo tumhari izzat bachane ka jigar bhi nahin rakta... Then the frightening transit of the knife point, with slow deliberation, from her wrist to her maang.. as he speaks of what really riles him.. Aur sochte rehna.. jis mohabbat se tum donon jude huye ho, asal mein us jazbat ki keemat kya hai? As far as the cowardly husband was concerned, nothing. And this is reflected in the tragic desolation in the eyes of the wife.

But that is not what is important. What is important is what this scene reveals about Jalal's bitterness towards the very idea of love. A bitterness rooted in what he sees as his abandonment by his parents, and especially by his mother, in his childhood and boyhood. Not all the protection and caring he gets from his Khan Baba and his Badiammi could, it seems, make up for this sense of not being wanted, not being his parents' first priority. A mistaken sense of neglect, maybe, but it is none the less real for all that.

It is the same bitterness that, in the scene between Jalal and his mother Hamida Bano that is due very soon, is so intense that it sears the screen.

Ok, folks, alvida till tomorrow!

Shyamala/Aunty/Akka/Di