This is surprisingly the only story in which there is no princess, Jack returns to his mother, and live with her, no princess to be rescued and married. When I did the research on this, I discovered that there is another version, where it Jack's actions of killing the Giant are not justified and this is surprisingly more close to the original one.

"Jack and the Beanstalk" is a Cornish fairy tale. It appeared as "The Story of Jack Spriggins and the Enchanted Bean" in 1734 and as Benjamin Tabart's moralised "The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk" in 1807. Henry Cole, publishing under pen name Felix Summerly popularised the tale in The Home Treasury (1845), and Joseph Jacobs rewrote it in English Fairy Tales (1890). Jacobs' version is most commonly reprinted today and it is believed to be closer to the oral versions than Tabart's because it lacks the moralising.

"Jack and the Beanstalk" is the best known of the "Jack tales", a series of stories featuring the archetypal Cornish hero and stock character Jack.

According to researchers at the universities in Durham and Lisbon, the story originated more than 5,000 years ago, based on a widespread archaic story form which is now classified by folkorists as ATU 328 The Boy Who Stole Ogre's Treasure.

Story

Jack is a young, poor boy living with his widowed mother and a dairy cow, on a farm cottage, the cow's milk as their only source of income. When the cow stops giving milk, Jack's mother tells him to take her to the market to be sold. On the way, Jack meets a bean dealer who offers magic beans in exchange for the cow, and Jack makes the trade. When he arrives home without any money, his mother becomes angry and disenchanted, throws the beans on the ground, and sends Jack to bed without dinner.

During the night, the magic beans cause a gigantic beanstalk to grow outside Jack's window. The next morning, Jack climbs the beanstalk to a land high in the sky. He finds an enormous castle and sneaks in. Soon after, the castle's owner, a giant, returns home. He senses that Jack is nearby by smell, and speaks a rhyme:

Fee-fi-fo-fum!

I smell the blood of an English man:

Be he alive, or be he dead,

I'll grind his bones to make my bread.

In the versions in which the giant's wife (the giantess), features, she persuades him that he is mistaken. When the giant falls asleep, Jack steals a bag of gold coins and makes his escape down the beanstalk.

Jack climbs the beanstalk twice more. He learns of other treasures and steals them when the giant sleeps: first a goose that lays golden eggs (see the idiom "to kill the goose that laid the golden eggs."), then a magic harp that plays by itself. The giant wakes when Jack leaves the house with the harp and chases Jack down the beanstalk. Jack calls to his mother for an axe and before the giant reaches the ground, cuts down the beanstalk, causing the giant to fall to his death.

Jack and his mother live happily ever after with the riches that Jack acquired.

The History of Beauty and the Beast

Beauty and the Beast, as far as fairy tales go, has a reasonably short history. Most fairy tales began as folklore, passed on from generation to generation, until they were eventually written down by collectors such as Giambattista Basile, Charles Perrault or the Brothers Grimm. Unusually, Beauty and the Beast does not appear in the anthologies of any of these authors (although the Grimms do have a reasonably similar version in The Singing Springing Lark). The tale has gone through many varied and imaginative incarnations, but remaining constant are the themes of envy unrewarded, of learning to love what may at first appear a beast' and the benefits which virtue and selflessness will bestow on the individual. Although the Beauty and the Beast' story certainly does incorporate folkloric elements (notably the Aarne-Thompson type of The Search for the Lost Husband') it has a discernable history, first starting with Madame Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve (1695 - 1755).

Villeneuve's Original Beauty and the Beast Story

Villeneuve was a French author influenced by Madame d'Aulnoy, Charles Perrault and various female intellectuals who gathered in the aristocratic salons. Originally published in La Jeune Amricaine, et Les Contes Marins in 1740, Villeneuve's La Belle et La Bte was an original piece of story telling. It was over one-hundred pages long, containing many subplots, and involving a genuinely savage, i.e. stupid' Beast, who suffered from not only his change of appearance. The book explored broader themes of romantic love as well as issues surrounding women's marital rights in the mid-eighteenth century. In this period, women had no choice over who they married (it was generally left to their fathers) and had to learn to love' the men they were bequeathed to.

Other French Variants of Beauty and the Beast

Villeneuve's Beauty and the Beast' story was later changed and shortened by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont (1711 - 1780) and published in Le Magasin des Enfants (1756). It is this version which readers are most familiar with today, although many elements were omitted from the original tale. Chiefly, in Villeneuve's account (and not in Beaumont's), the back-story of both Belle and the Beast is given. The Beast was a prince who lost his father at a young age, and whose mother had to wage war to defend his kingdom. The queen left him in care of an evil fairy, who tried to seduce him when he became an adult; when he refused, she transformed him into a beast. Belle's story reveals that she is not really a merchant's daughter but the offspring of a king and a good fairy. The wicked fairy had tried to murder Belle so she could marry her father the king, and Belle was put in the place of a merchant's dead daughter to protect her.

Beaumont significantly pared down the cast of characters of Beauty and the Beast' and simplified the tale to an almost archetypal simplicity; much loved and repeated. The change from Belle as the offspring of a king and a fairy, to Belle as a simple merchant's daughter is very telling. Beaumont's version, starting with an urban setting is highly unusual in fairy tales, as is the social class of the characters, neither royal nor peasants. Such details reflect the vast social upheavals occurring in France at the time; with the story published just thirty-three years before the French Revolution. This period marked the decline of the powerful monarchy and the church, and the concomitant rise of democracy and nationalism. Popular resentment of the privileges enjoyed by the clergy and aristocracy grew amidst a financial crisis following two expensive wars and years of bad harvests - with demands for change couched in terms of Enlightenment ideals. That the heroine of La Belle et La Bte is a simple, working class girl - able to tame the aristocratic beast, spoke directly to the social concerns of the day.

Cupid and Psych - The First Ever Literary Fairy Tale

Despite these discernable French Enlightenment' beginnings, Bruno Bettelheim has noted in The Uses of Enchantment that this story most likely derives from Cupid and Psyche, the ancient chronicle from the Latin novel Metamorphoses, written in the Second Century CE by Apuleius. It concerns the overcoming of obstacles to love between Psyche (meaning Soul', or Breath of Life') and Cupid (meaning Desire') and their ultimate union in marriage. The myth of cupid and psyche is one of the oldest tales to evidence the search for the lost husband' trope, and is considered by many scholars to be the first ever literary fairy tale. The similarities between this legend and Villeneuve's Beauty and the Beast' are so striking, it is very likely to be a direct descendant.

The Ancient Roman tale starts with Psyche's banishment (by the jealous Venus) to a mountaintop, in order to be wed to a murderous beast. Sent to destroy her, Cupid falls in love and flies her away to his castle. There she is directed to never seek to see the face of her husband, who visits and makes love to her in the dark of night. Eventually Psyche succumbs to her curiosity (prompted by her selfish sisters), but accidentally scars her husband with a candle. In attempted atonement, Psyche offers herself as a slave to Venus, and completes a set of impossible tasks. Completing the last task (seeking beauty from the Queen of the Underworld), Psyche opens the beauty in a box' and, hoping to gain the approval of her husband, opens the box a little - at once falling into a coma. Overcome with grief, Cupid rescues her. He begs Jupiter that she may become immortal, so that the two could be forever united. Here, instant resemblances can be seen with the character of the beast, banishment to a castle, the deceptive sisters, and true love (mixed with tragedy) ensuring the pair's eternal union.

Beauty and The Beast Worldwide

Even with this tale's ancient beginnings, Apuleius might also have drawn on earlier, oral renditions of the tale from Greek versions; and the Greeks, in turn, may have derived their story from Asian sources since Cupid and Psyche' closely reflects the narrative of The Woman Who Married a Snake.' This variant first appeared in the Indian Panchatantra, a work known to have existed in oral form well before its appearance in print in 500 AD. This helps to explain later Beauty and the Beast' variants, where the French beast is replaced by a snake (in the Russian, Chinese and Greek versions), and others - for example in the English variant written by Sidney Oldall Addy, where the beast' is a Small-tooth dog', a Danish narrative of Beauty and the Horse', and the Swiss variant of The Bear Prince.' Despite these intriguing discrepancies in the narrative, the best known English version (published by Andrew Lang in 1889) stays with the French roots, representing a complex mix of Villeneuve's and Beaumont's stories.

J. R. Planch and Andrew Lang - English Versions

Lang largely favours Villeneuve's elements of the story (hence its inclusion in this collection, along with Beaumont's account), but also edits out much of the extra dialogue concerning fairies and genealogies. There is another (older) English translation in evidence, that of J. R. Planch (published in 1757), which altered a small but significant part. Instead of asking Belle to marry him each night, the Beast asks: May I sleep with you tonight?' The question, whilst obviously more risque, was not simply erotic. It served to imply control and choice for Belle over her own body and sexuality - something which at that time was not legally hers, nor of any woman handed over as property to her husband. This overt sexuality is repeated in the Russian tale of The Enchanted Tsarevich, and the Chinese recitation of The Fairy Serpent. In most, the beast is no true beast and never forces his physical desires upon the woman. The Italian narrative of Zelinda and the Monster differs in this respect, as the snake persuades the young girl to marry him, only because her father will die if she refuses.

As a testament to this story's ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, the tale of Beauty and the Beast continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. It has inspired some of the best fairy tale adaptations in film, from Jean Cocteau's 1946 masterpiece to Disney's Beauty and the Beast (1991), a nominee and winner for Best Motion Picture' by several Hollywood organisations. With regard to its wide geographical reach, as is evident from even this brief introduction, it has enthused and affected storytelling all over the globe. The story has been translated into almost every language, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.

~Source: http://www.pookpress.co.uk/project/beauty-and-the-beast-history/~

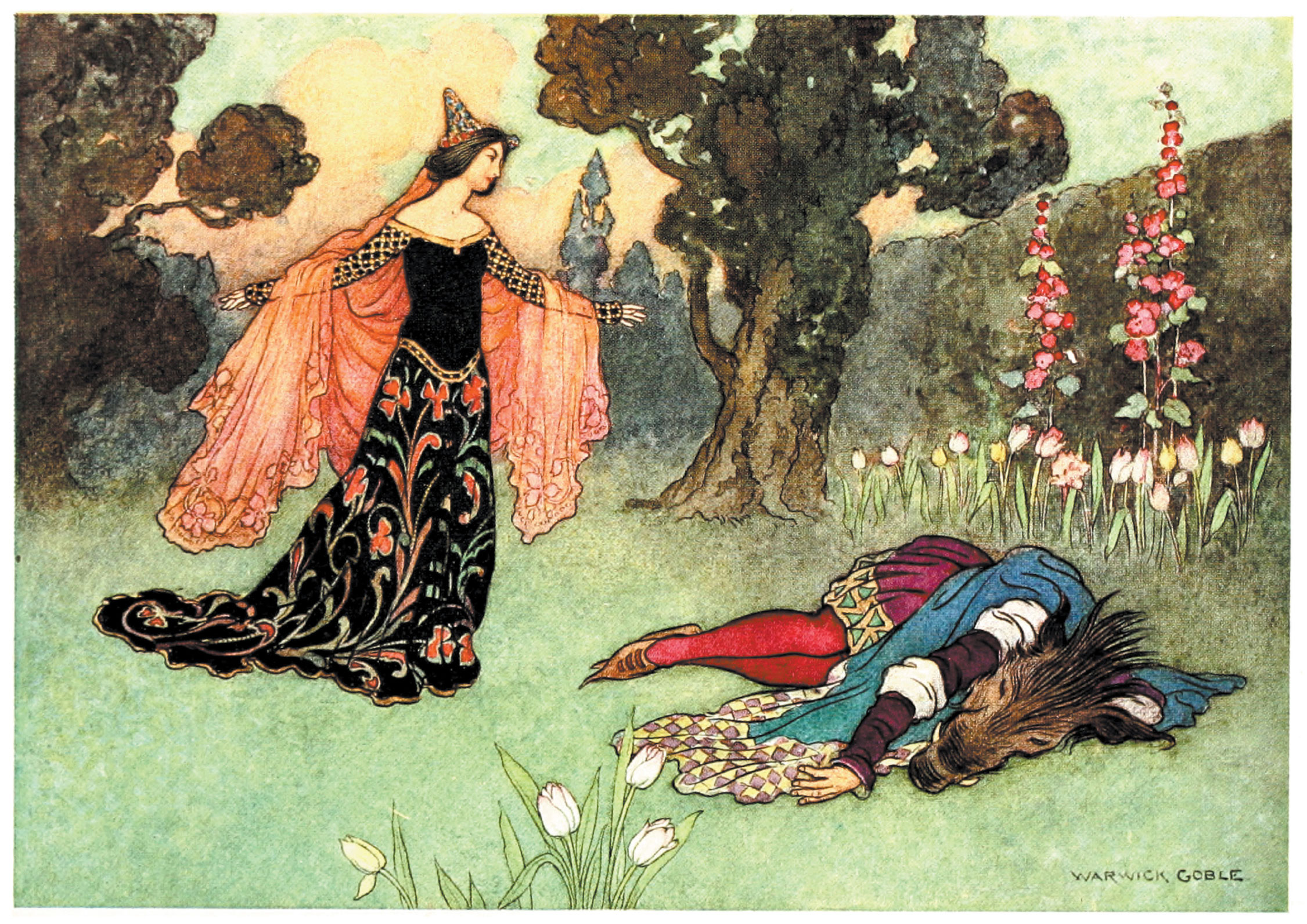

Below is the illustration for one of the fairy tale retellings:

I have not watched any of Disney's film versions of the above, but a reading of the same lets me know that the story has been changed to included a good looking suitor, thus having Beauty to choose between a good looking corrupt husband or a ugly beast with a heart of gold. Her attributes in all the stories are beauty and goodness, which are sort of synonymous and which is something that has the feminists up in arms😆

But then I do love the lines of the song - "A Tale as old as Time, A Song as old as Rhyme" -aahhh the feels

________________________________________________________________________________

This is an original story by Hans Christian Anderson, with very clear biblical references that were subsequently toned down. This is also a very long story, consisting of seven distinctive sub stories, all featuring Gerda, the main female protagonist.

By the time he sat down to pen "The Snow Queen" in the early 1840s, Hans Christian Andersen had already published two collections of fairy tales, along with several poems that had achieved critical recognition. Fame and fortune still eluded him, however, and would until his fairy tales began to be translated into other languages.

"The Snow Queen" was his most ambitious fairy tale yet, a novella-length work that rivaled some of the early French salon fairy tales for its intricacy. Andersen, inspired by the versions of The One Thousand and One Nights that he'd encountered, worked with their tale-within-a-tale format, carefully and delicately using images and metaphor to explore the contrasts between intellect and love, reality and dream; he also gently critiqued both stories. The result was to be lauded as one of Andersen's masterpieces.

Its biggest inspiration was the Norwegian fairy tale East of the Sun, West of the Moon. Like Beauty and the Beast, this is another retelling of Cupid and Psyche. Andersen probably heard a Danish version from his grandmother; he may also have encountered one of the tale's many written forms.

Basically, the theme of East of the Sun, West of the Moon is that life really, genuinely sucks and is extremely unfair: here, the result of obeying her parents (her mother tells her to use the light) and trying, you know, to find out what exactly is in bed with her leads to endless months of wandering around the cold, cold north, even if she does get help from three old women and the winds along the way.

Andersen took this story, with its themes of transformation, sacrifice, long journeys and unfairness, and chose to twist several elements of it, adding themes of temptation and philosophy and intellect and Christian love and charity.

"The Snow Queen" is told in a series of seven stories. In the first, a troll (in some English translations, a "hobgoblin," "demon," or "devil") creates a mirror that distorts beauty. The mirror breaks, sending fragments of its evil glass throughout the world, distorting people's vision, making them only able to see the worst in everything. The troll laughs"

"and that's pretty much the last we hear of the troll, setting up a pattern that continues throughout the novella: in this fairy tale, evil can and does go unpunished. It was, perhaps, a reflection of Andersen's own experiences, and certainly a theme of many of his stories. By 1840, he had witnessed many people getting away with cruel and unkind behavior, and although he was certainly more than willing to punish his own protagonists, even overly punish his own protagonists, he often allowed the monsters of his stories to go unpunished. When they could even be classified as monsters.

The second story shifts to little Kay and Gerda, two young children living in cold attics, who do have a few joys in life: the flowers and roses that grow on the roofs of their houses, copper pennies that they can warm on a stove and put on their windows, melting the ice (a lovely touch), and the stories told by Kay's grandmother. At least some of these details may have been pulled from Andersen's own memories: he grew up poor, and spent hours listening to the stories told by his grandmother and aunts.

Kay sees the Snow Queen at the window, and shortly afterwards, fragments of the mirror enter his heart and eye, transforming him from a little boy fascinated with roses and fairy tales into a clever, heartless boy who likes to tease people. He abandons Gerda and the joy of listening to stories while huddled near a warm stove to go out and play with the older boys in the snow. He fastens his sled to a larger one that, it turns out, is driven by the Snow Queen. She pulls him into her sled and kisses him on the forehead. He forgets everything, and follows her to the north.

The text rather strongly hints that this is a bit more than your typical journey to visit the fjords. Not just because the Snow Queen is a magical creature of ice and snow, but because the language used to describe the scene suggests that Kay doesn't just freeze, but freezes to death: he feels that he is sinking into a snow drift and falling to sleep, the exact sensations reported by people who almost froze to death, but were revived in time. Gerda, indeed, initially believes that little Kay must be dead. 19th century writers often used similar language and images to describe the deaths of children, and George MacDonald would later use similar imagery when writing At the Back of the North Wind.

On a metaphorical level, this is Andersen's suggestion that abandoning love, or even just abandoning stories, is the equivalent of a spiritual death. On a plot level, it's the first echo of East of the Sun, West of the Moon, where the prince is taken to an enchanted castle"or, if you prefer, Death. Only in this case, Kay is not a prince, but a boy, and he is not enchanted because of anything that Gerda has done, but by his own actions.

In the third story, with Kay gone, Gerda starts to talk to the sunshine and sparrows (not exactly an indication of a stable mental state), who convince her that Kay is alive. As in East of the Sun, West of the Moon, she decides to follow him, with the slight issue that she has no real idea where to look. She begins by trying to sacrifice her red shoes to the river (Andersen appears to have had a personal problem with colorful shoes), stepping into a boat to do so. The boat soon floats down the river, taking Gerda with it. Given what happens next, it's possible that Gerda, too, has died by drowning, but the language is rich with sunshine and life, so possibly not. Her first stop: the home of a lonely witch, who feeds Gerda enchanted food in hopes that the little girl will stay.

The witch also has a garden with rather talkative flowers, each of which wants to tell Gerda a story. Gerda's response is classic: "BUT THAT DOESN'T TELL ME ANYTHING ABOUT KAY!" giving the distinct impression that she's at a cocktail party where everyone is boring her, in what seems to be an intentional mockery of intellectual parties that bored Andersen to pieces. Perhaps less intentionally, the scene also gives the impression that Gerda is both more than a bit self-centered and dim, not to mention not all that mentally stable"a good setup for what's about to happen in the next two stories.

In the fourth story, Gerda encounters a crow, a prince, and a princess. Convinced that the prince is Kay, Gerda enters the palace, and his darkened bedroom, to hold up a lamp and look at his face. And here, the fairy tale is twisted: the prince is not Gerda's eventual husband, but rather a stranger. The story mostly serves to demonstrate again just how quickly Gerda can jump to conclusions"a lot of people wear squeaky boots, Gerda, it's not exactly proof that any of them happen to be Kay!"but it's also a neat reversal of the East of the Sun, West of the Moon in other ways: not only is the prince married to his true bride, not the false one, with the protagonist misidentifying the prince, but in this story, rather than abandoning the girl at the beginning of her quest, after letting her spend the night in the prince's bed (platonically, we are assured, platonically!) the prince and princess help Gerda on her way, giving her a little sled, warm clothing and food for the journey.

Naturally, in the fifth tale she loses pretty much all of this, and the redshirt servants sent along with her, who die so rapidly I had to check to see if they were even there, when she encounters a band of robbers and a cheerful robber girl, who tells Gerda not to worry about the robbers killing her, since she"that is, the robber girl"will do it herself. It's a rather horrifying encounter, what with the robber girl constantly threatening Gerda and a reindeer with a knife, and a number of mean animals, and the robber girl biting her mother, and then insisting that Gerda sleep with her"and that knife. Not to say that anything actually happens between Gerda and the girl, other than Gerda not getting any sleep, but it's as kinky as this story gets, so let's mention it.

The next day, the robber girl sends Gerda off to the sixth tale, where she encounters two more old women"for a total of three. All three tend to be considerably less helpful than the old women in East of the Sun, West of the Moon: in Andersen's version, one woman wants to keep Gerda instead of helping her, one woman can't help all that much, and the third sends the poor little girl off into the snow without her mittens. Anyway, arguably the best part of this tale is the little details Andersen adds about the way that one of the women, poverty stricken, writes on dried fish, instead of paper, and the second woman, only a little less poverty stricken, insists on eating the fish EVEN THOUGH IT HAS INK ON IT like wow, Gerda thought that sleeping with the knife is bad.

This tale also has my favorite exchange of the entire story:

"...Cannot you give this little maiden something which will make her as strong as twelve men, to overcome the Snow Queen?"

"The Power of twelve men!" said the Finland woman. "That would be of very little use."

What does turn out to be of use: saying the Lord's Prayer, which, in an amazing scene, converts Gerda's frozen breath into little angels that manage to defeat the living snowflakes that guard the Snow Queen's palace, arguably the most fantastically lovely metaphor of praying your way through terrible weather ever.

And then finally, in tale seven, Gerda has the chance to save Kay, with the power of her love, her tears, and her prayers finally breaking through the cold rationality that imprisons him, showing him the way to eternity at last. They return home, hand in hand, but not unchanged. Andersen is never clear on exactly how long the two were in the North, but it was long enough for them both to age into adulthood, short enough that Kay's grandmother is still alive.

Despite the happy ending, a sense of melancholy lingers over the story, perhaps because of all the constant cold, perhaps because of the ongoing references to death and dying, even in the last few paragraphs of the happy ending, perhaps because the story's two major antagonists"the demon of the first tale, the Snow Queen of the last six tales"not only don't die, they're never even defeated. The Snow Queen"conveniently enough"happens to be away from her castle when Gerda arrives. To give her all due credit, since she does seem to have at least some concern for little Kay's welfare"keeping him from completely freezing to death, giving him little math puzzles to do, she might not even be all that displeased to find that Gerda saved him"especially since they leave her castle untouched.

The platonic ending also comes as a bit of a jolt. Given the tale's constant references to "little Gerda" and "little Kay," it's perhaps just as well"a few sentences informing me that they're adults isn't really enough to convince me that they're adults. But apart from the fact that Gerda spends an astonishing part of this story jumping in and out of people's beds, making me wonder just how much the adult Gerda would hold back from this, "The Snow Queen" is also a fairy tale about the power of love, making it surprising that it doesn't end in marriage, unlike so many of the fairy tales that helped inspire it.

But I think, for me, the larger issue is that, well, this defeat of reason, of intellectualism by love doesn't quite manage to ring true. For one thing, several minor characters also motivated by love"some of the flowers, and the characters in their tales, plus the crow"end up dead, while the Snow Queen herself, admirer of mathematics and reason, is quite alive. For another thing, as much as Kay is trapped by reason and intellectualism as he studies a puzzle in a frozen palace, Gerda's journey is filled with its own terrors and traps and disappointments, making it a little tricky for me to embrace Andersen's message here. And for a third thing, that message is more than a bit mixed in other ways: on the one hand, Andersen wants to tell us that the bits from the mirror that help trap little Kay behind ice and puzzles prevent people from seeing the world clearly. On the other hand, again and again, innocent little Gerda"free of these little bits of glass"fails to see things for what they are. This complexity, of course, helps add weight and depth to the tale, but it also makes it a bit harder for the ending to ring true.

And reading this now, I'm aware that, however much Andersen hated his years at school, however much he resented the intellectuals who dismissed his work, however much he continued to work with the fairy tales of his youth, that education and intellectualism was what eventually brought him the financial stability and fame he craved. He had not, to be fair, gained either as he wrote "The Snow Queen," which certainly accounts for the overt criticism of rationality, intellectualism and, well, math, and he was never to emotionally recover from the trauma of his education, and he had certainly found cruelty and mockery amongst the intellectuals he'd encountered, examples that helped shape his bitter description of Kay's transformation from sweet, innocent child to cruel prankster. At the same time, that sophistication and education had helped transform his tales.

But for young readers, "The Snow Queen" does have one compelling factor: it depicts a powerless child triumphing over an adult. Oh, certainly, Gerda gets help along the way. But notably, quite a lot that help comes from marginalized people"a robber, two witches, and two crows. It offers not just a powerful argument that love can and should overcome reason, but the hope that the powerless and the marginalized can triumph. That aspect, the triumph of the powerless, is undoubtedly why generations have continued to read the tale, and why Disney, after several missteps, transformed its core into a story of self-actualization.

~Source: Article by Mari Ness for http://www.tor.com/2016/06/23/fairy-tale-subversion-hans-christian-andersens-the-snow-queen/~

"Rapunzel" is a German fairy tale in the collection assembled by the Brothers Grimm, and first published in 1812 as part of Children's and Household Tales. The Grimm Brothers' story is an adaptation of the fairy tale Rapunzel by Friedrich Schulz published in 1790. The Schulz version is based on Persinette by Charlotte-Rose de Caumont de La Force originally published in 1698, which in turn was influenced by an even earlier tale, Petrosinella by Giambattista Basile, published in 1634. Its plot has been used and parodied in various media and its best known line ("Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair") is an idiom of popular culture. In volume I of the 1812 annotations (Anhang), it is listed as coming from Friedrich Schulz Kleine Romane, Book 5, pp. 269-288, published in Leipzig 1790.

In the Aarne-Thompson classification system for folktales it is type 310, "The Maiden in The Tower".

Andrew Lang included it in The Red Fairy Book. Other versions of the tale also appear in A Book of Witches by Ruth Manning-Sanders and in Paul O. Zelinsky's 1997 Caldecott Medal-winning picture book, Rapunzel and the Disney movie Tangled.

Rapunzel's story has striking similarities to the 11th-century Persian tale of Rudba, included in the epic poem Shahnameh by Ferdowsi. Rudba offers to let down her hair from her tower so that her lover Zl can climb up to her. Some elements of the fairy tale might also have originally been based upon the tale of Saint Barbara, who was said to have been locked in a tower by her father.

Plot

A lonely couple, who want a child, live next to a walled garden belonging to an evil witch named Dame Gothel. The wife, experiencing the cravings associated with the arrival of her long-awaited pregnancy, notices some rapunzel (or, in most translated-to-English versions of the story, rampion), growing in the garden and longs for it, desperate to the point of death. One night, her husband breaks into the garden to get some for her. She makes a salad out of it and greedily eats it. It tastes so good that she longs for more. So her husband goes to get some more for her. As he scales the wall to return home, Dame Gothel catches him and accuses him of theft. He begs for mercy, and she agrees to be lenient, and allows him to take all the rapunzel he wants, on condition that the baby be given to her when it's born. Desperate, he agrees. When his wife has a baby girl, Dame Gothel takes her to raise as her own and names her Rapunzel after the plant her mother craved. She grows up to be the most beautiful child in the world with long golden hair. When she turns twelve, Dame Gothel lockes her up inside a tower in the middle of the woods, with neither stairs nor a door, and only one room and one window. When she visits her, she stands beneath the tower and calls out:

Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair, so that I may climb thy golden stair.

One day, a prince rides through the forest and hears Rapunzel singing from the tower. Entranced by her ethereal voice, he searches for her and discovers the tower, but is naturally unable to enter it. He returns often, listening to her beautiful singing, and one day sees Dame Gothel visit, and thus learns how to gain access to Rapunzel. When Dame Gothel leaves, he bids Rapunzel let her hair down. When she does so, he climbs up, makes her acquaintance, and eventually asks her to marry him. She agrees.

Together they plan a means of escape, wherein he will come each night (thus avoiding Dame Gothel who visits her by day), and bring Rapunzel a piece of silk, which she will gradually weave into a ladder. Before the plan can come to fruition, however, she foolishly gives him away. In the first edition of Grimm's Fairy Tales, she innocently says that her dress is getting tight around her waist (indicating pregnancy); in the second edition, she asks Dame Gothel (in a moment of forgetfulness) why it is easier for her to draw up the prince than her. In anger, she cuts off Rapunzel's hair and casts her out into the wilderness to fend for herself.

When the prince calls that night, Dame Gothel lets the severed hair down to haul him up. To his horror, he finds himself staring at her instead of Rapunzel, who is nowhere to be found. When she tells him in a jealous rage that he will never see Rapunzel again, he leaps from the tower and lands on some thorns, which blind him.

For months, he wanders through the wastelands of the country and eventually comes to the wilderness where Rapunzel now lives with the twins she has given birth to, a boy and a girl. One day, as she sings, he hears her voice again, and they are reunited. When they fall into each other's arms, her tears immediately restore his sight. He leads her and their twins to his kingdom, where they live happily ever after.

In some versions of the story, Rapunzel's hair magically grows back after the prince touches it.

Another version of the story ends with the revelation that Dame Gothel had untied Rapunzel's hair after the prince leapt from the tower, and it slipped from her hands and landed far below, leaving her trapped in the tower.

The seemingly uneven bargain with which "Rapunzel" opens is a common trope in fairy tales which is replicated in "Jack and the Beanstalk", Jack trades a cow for beans, and in "Beauty and the Beast", Beauty comes to the Beast in return for a rose. Folkloric beliefs often regarded it as quite dangerous to deny a pregnant woman any food she craved. Family members would often go to great lengths to secure such cravings. Such desires for lettuce and like vegetables may indicate a need on her part for vitamins.

An influence on Grimm's Rapunzel was Petrosinella or Parsley, written by Giambattista Basile in his collection of fairy tales in 1634, Lo c**to de li c**ti (The Story of Stories), or Pentamerone. This tells a similar tale of a pregnant woman desiring some parsley from the garden of an ogress, getting caught, and having to promise the ogress her baby. The encounters between the prince and the maiden in the tower are described in quite bawdy language. A similar story was published in France by Mademoiselle de la Force, called "Persinette". As Rapunzel did in the first edition of the Brothers Grimm, Persinette becomes pregnant during the course of the prince's visits.

Literary adaptations

Anne Sexton wrote an adaptation as a poem called "Rapunzel" in her collection Transformations (1971), a book in which she re-envisions sixteen of the Grimm's Fairy tales.

Cress the third book in the Lunar Chronicles is a young adult science fiction adaptation of Rapunzel written by Marissa Meyer. Crescent, aka "Cress" is a prisoner on a satellite who is rescued and falls in love with her hero "Capt. Thorn" amidst the story about "Cinder" a cyborg version of Cinderella. Lunar Chronicles is a tetralogy with a futuristic take on classic fairytales which also include characters such as "Cinder" (Cinderella), "Scarlet" (Red Riding Hood) " and "Winter" (Snow White).

Kate Forsyth has written a book that contains both commentary on the story and a retelling, set in the Antipodes. She described it as "a story that reverberates very strongly with any individual -- male or female, child or adult -- who has found themselves trapped by their circumstances, whether this is caused by the will of another, or their own inability to change and grow".

This story has been told too many times and I shall reproduce only the trivia associated with it below:

Cinderella, or The Little Glass Slipper, (Italian: Cenerentola, French: Cendrillon, ou La petite Pantoufle de Verre, German: Aschenputtel) is a folk tale embodying a myth-element of unjust oppression/triumphant reward. Thousands of variants are known throughout the world. The title character is a young woman living in unfortunate circumstances, that are suddenly changed to remarkable fortune. The story of Rhodopis, recounted by the Greek geographer Strabo in around 7 BC, about a Greek slave girl who marries the king of Egypt, is considered the earliest known variant of the "Cinderella" story. The most popular version was first published by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps passe in 1697, and later by the Brothers Grimm in their folk tale collection Grimms' Fairy Tales.

Although the story's title and main character's name change in different languages, in English-language folklore "Cinderella" is the archetypal name. The word "Cinderella" has, by analogy, come to mean one whose attributes were unrecognized, or one who unexpectedly achieves recognition or success after a period of obscurity and neglect. The still-popular story of "Cinderella" continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions, and tropes to a wide variety of media. The Aarne-Thompson system classifies Cinderella as "the persecuted heroine".

Ancient and international versions

The Aarne-Thompson system classifies Cinderella as type 510A, "the persecuted heroine". Variants of the theme are known throughout the world.

Ancient Greece

The oldest known version of the Cinderella story is the ancient Greek story of Rhodopis, a Greek courtesan living in the colony of Naucratis in Egypt, whose name means "Rosy-Cheeks." The story is first recorded by the Greek geographer Strabo in his Geographica (book 17, 33), probably written around 7 BC or thereabouts:

They tell the fabulous story that, when she was bathing, an eagle snatched one of her sandals from her maid and carried it to Memphis; and while the king was administering justice in the open air, the eagle, when it arrived above his head, flung the sandal into his lap; and the king, stirred both by the beautiful shape of the sandal and by the strangeness of the occurrence, sent men in all directions into the country in quest of the woman who wore the sandal; and when she was found in the city of Naucratis, she was brought up to Memphis, became the wife of the king .

The same story is also later reported by the Roman orator Aelian (ca. 175-ca. 235) in his Miscellanious History, which was written entirely in Greek. Aelian's story closely resembles the story told by Strabo, but adds that the name of the pharaoh in question was Psammetichus. Aelian's account indicates that the story of Rhodopis remained popular throughout antiquity.

Herodotus, some five centuries before Strabo, records a popular legend about a possibly-related courtesan named Rhodopis in his Histories, claiming that Rhodopis came from Thrace, and was the slave of Iadmon of Samos, and a fellow-slave of the story-teller Aesop and that she was taken to Egypt in the time of Pharaoh Amasis, and freed there for a large sum by Charaxus of Mytilene, brother of Sappho the lyric poet.

China

A version of the story, Ye Xian, appeared in Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang by Duan Chengshi around 860. Here, the hardworking and lovely girl befriends a fish, the rebirth of her mother. The fish is later killed by her stepmother and sister. Ye Xian saves the bones, which are magic, and they help her dress appropriately for the New Year Festival. When she loses her slipper after being recognized by her stepfamily, the king finds her slipper and falls in love with her (eventually rescuing her from her cruel stepmother).

Indonesia and Malaysia

The Indonesian and Malaysian story Bawang Merah Bawang Putih, are about two girls named Bawang Putih (literally "White Onion", meaning "garlic") and Bawang Merah ("Red Onion"). While the two country's respective versions differ in the exact relationship of the girls and the identity of the protagonist, they have highly similar plot elements. Both have a magical fish as the "fairy godmother" to her daughter, which the antagonist cooks. The heroine then finds the bones and buries them, and over the grave a magical swing appears. The protagonist sits on the swing and sings to make it sway, her song reaching the ears of a passing Prince. The swing is akin to the slipper test, which distinguishes the heroine from her evil sister, and the Prince weds her in the end.

In Indonesia, Bawang Putih is the kind-hearted girl, who suffers at the hands of her evil stepmother, and stepsister Bawang Merah, who is the one that cooks the fish-mother. When the Prince enquires after the singer on the swing, Bawang Merah lies, but is proven false when cannot make the magical swing move. The angry prince forces Bawang Merah and her mother to tell the truth. They then admit that there is another daughter in the house. Bawang Putih comes out and moves the magical swing by her singing. In the end, she and her prince marry and live happily ever after.

In the Malaysian version, it is Bawang Merah and her mother Mak Labu ("Mother Gourd") who are good, while her half sister Bawang Putih and her mother Mak Kundur ("Mother Wintermelon") are evil. Both mothers were the wives of a poor man, and upon his death Mak Kundur seized control of the household and forced Mak Labu and Bawang Merah to do all the chores around the house. One day as Mak Labu was fetching water at the well, Mak Kundur pushed her into it, and Mak Labu turns into a gourami. In this version, Mak Kundur killed the fish and fed it to Bawang Merah who learns of her mother's fishbones in a dream and finds them with the aid of some ants. Bawang Merah gathers the fish bones and buries them in a small grave underneath a tree. When she visits the grave the next day, she is surprised to see that a beautiful swing has appeared from one of the tree's branches. When Bawang Merah sits in the swing and sings an old lullaby, it magically swings back and forth. In this version, Mak Kundur knows the Prince, and lies when a royal guard enquires after the girl on the swing. Bawang Merah sings and it is she whom the Prince marries at the end of the story.

Philippines

Another version also exists in the Philippines, probably handed by the Spaniards. Here, the girl is either named Maria (in most versions), Peregrina or Catherine in other versions. She is given impossible tasks but is helped by a crab in most versions, a fish in the Visayan regions or the Virgin Mary in the Luzon variants. The cruel relatives are not only limited to her stepfamily, but extends to her aunt and cousins, or her jealous godmother. The Cinderella figure however, is more independent, as she shapes her future in her own hands. She does not always have a royal marriage in the end, but rather emerges as a rich and successful young woman overcoming all the cruelties she had suffered. However, due to later influences, the prince or king or simply a wealthy bachelor is added to the story, as well as the ball (or church service) and the missing shoe.

Vietnam

In the Vietnamese version Tam Cam, Tam is mistreated by both her father's co-wife and half-sister. After her fishing achievements are unjustly stolen by the stepsister, she brings the only remaining fish home and feeds it as a pet. Her jealous step-family kills the fish and eats it, but its bones continue to serve as her protector and guardian, eventually leading her to become the king's bride during a festival. The protagonist takes violent revenge in part two of the story; after being murdered four times by her stepmother and stepsister, she eventually comes back from the dead and boils her stepsister alive, indirectly resulting in the death of her stepmother.

Korea

The Korean version of the story, Kongjwi and Patjwi, tells of a kind girl named Kongjwi, who is constantly abused by her stepmother and stepsister Patjwi. The step-family forces Kongjwi to stay at home while they attend the king's festival, asking her to repair a leaking jar. A toad assists with the jar, and an ox brings her clothes for the festival. The story contains the same general motifs as most other versions of the story, including a festival and a king who falls in love with the protagonist.

West and South Asia

Several different variants of the story appear in the medieval One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights, including "The Second Shaykh's Story", "The Eldest Lady's Tale" and "Abdallah ibn Fadil and His Brothers", all dealing with the theme of a younger sibling harassed by two jealous elders. In some of these, the siblings are female, while in others, they are male. One of the tales, "Judar and His Brethren", departs from the happy endings of previous variants and reworks the plot to give it a tragic ending instead, with the younger brother being poisoned by his elder brothers.

Britain

Aspects of Cinderella may be derived from the story of Cordelia in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae. Cordelia is the youngest and most virtuous of King Leir of Britain's three daughters, however her virtue is such that it will not allow her to lie in flattering her father when he asks, so that he divides up the kingdom between the elder daughters and leaves Cordelia with nothing. Cordelia marries her love, Aganippus, King of the Franks, and flees to Gaul where she and her husband raise an army and depose her wicked sisters who have been misusing their father. Cordelia is finally crowned Queen of Britain. However her reign only lasts five years. The story is famously retold in Shakespeare's King Lear, but given a tragic ending.

The Charles Dickens novel David Copperfield also shares similarities with Cinderella, but is gender reversed; David, a young boy, has a passive mother who remarries with a cruel man after her husband passes.

The Middle East

Variants from Iran and Arabian countries also exist, one titled as the Maah Pishnih which means "The Girl With The Moon On Her Forehead". In this version, the Cinderella figure is both benevolent and malevolent; she murders her own mother inside a vinegar jar so that her father can marry the neighborhood Quran instructress. From this cruel act, the girl gains a cruel stepmother and an imbecile stepsister. She befriends either a cow (her mother's spirit/reincarnation), a fish (sent by her mother or Allah), or a 1000 year old demoness living underground which becomes her helper. After accomplishing a series of tasks for the wicked second wife, she is rewarded with a moon-shaped jewel on her forehead and a star on her chin, or long golden hair, while the other sister is cursed with ugliness. The story culminates with the monarch announcing a celebration, which the heroine attends. Either the king's son or the king himself falls in love with her immediately after seeing her face. Out of either shame or terror (as Islamic women are supposed to be reserved before men), the girl leaves hastily, leaving behind one of her golden shoes, which is given to her along with clothes and transportation by her spiritual helper. The monarch in the story asks for help from female relatives (mostly his mother the Sultana) and the relative tries the shoe on every woman in the land. The stepfamily tries to sabotage everything, but a rooster usually betrays them. The story ends with Maah Pishnih becoming a royal bride, and her entire family being put to death.

~Source: Wikipedia~

Surprisingly, there are no Indian variations of this tale

East of the Sun and West of the Moon is a Norwegian fairy tale collected by Peter Christen Asbjrnsen and Jorgen Moe.

It involves a white bear that offers to take the youngest child to fix a family's poor situation. They accept and the bear takes the young girl to a castle where a man slept in the same room as her at night in the dark. As such, she could not see who it was. When she was homesick she was allowed to go home with one condition: She is not allowed to stay with her mother alone. Of course, the young girl doesn't listen and takes a magical candle from her mother. When she returned to the castle, she was able to see the face of the man that has been visiting her bed at night " who was actually the bear. After a what have you done moment he gets taken away by his troll stepmother to marry a troll princess. Before leaving, he tells her that he will be at a land East of the Sun and West of the Moon.

She sets off to find him and meets a woman and her daughter on the way. This woman gives her a golden apple and lets her borrow a horse. Next, she meets a woman who gives her a golden carding comb. A third woman gives her a golden spinning wheel and tells her that she should go find the east wind who might take her to the place that she seeks. The east wind could not help her as he never blew that far so he tells her to visit the west. After facing the same scenario, she visits the south and finally the north wind. The girl then gives up all of her golden items to the princess in exchange for a night with the prince. On the first two nights, she could not wake him. Eventually the servants tell the prince about the girl and he tosses away the drink " actually sleeping potion " from the princess that night. In the end, the girl defeats the trolls (the stepmother and the princess) by washing out the tallow of one of the prince's shirts, because the prince refuses to marry someone unable to do something so simple. The story ends with all the trolls exploding. Everyone lives happily ever after.

It's Aarne-Thompson type 425A, the search for the lost husband, a type of which there are many variants. Compare The Feather of Finist the Falcon and Pintosmalto, and for the Gender Flip Soria Moria Castle and The Blue Mountains.

The tale, with all related versions, is reckoned to be related to the tale of Amor and Psyche, as re-told in the book The Golden Ass by the author Apuleius, from the Roman era. This version is probably the Ur-Example of the story. As everyone will understand, the girl has the role of Psyche, while the prince has the role of Amor.

For a modern novel version, see East by Edith Pattou or Once Upon a Winters Night by Dennis L. McKiernan. There is also one that adds in some Inuit legends into the mix called ICE by Sarah Beth Durst.

A number of famous illustrated versions of this fairy tale have been published, including by Mercer Mayer, among others. All of the versions are slightly different. Do not confuse with the Haruki Murakami book South of the Border, West of the Sun.

Tropes in East of the Sun and West of the Moon:

Animorphism / Involuntary Shapeshifting: The result of a Curse placed upon the prince by his Wicked Stepmother.

Beast and Beauty: For a while.

Big Fancy Castle: Where the bear takes her.

Color-Coded for Your Convenience: In this and many of the story variations, the groom's animal form is often white. This ties into the cross-cultural concept that white animals are believed to have magical properties.

Curse

Curse Escape Clause

Disproportionate Retribution: Poor girl makes one mistake, then must trek all over Scandinavia to right it.

Dogged Nice Guy: The groom, who is always described as treating his bride extremely well when they get to his palace"servants to tend to her every need, great food, etc. This is a strange variant in that he already has the girl; she's just repulsed by his animal appearance.

Earn Your Happy Ending: And how!

If I Can't Have You...: The groom is cursed because he won't marry another princess, who is unpleasant and often hideous.

Involuntary Shapeshifting

It Was a Gift

Nice Job Breaking It, Hero!: While it's understandable that the bride's parents would feel squicked that she's married a bear/wolf/some other huge and intimidating animal, they often have an iron grip on that Idiot Ball when the bride herself isn't carrying it.

The Quest: The wife has to search for her husband by going east of the sun and west of the moon. This may or may not be an allegory for finding a nonexistent place through The Power of Love.

Textile Work Is Feminine: The final thing she had to do was wash his shirt clean.

Villainesses Want Heroes: The troll bride.

What Beautiful Eyes!: The prince nearly always has gorgeous blue eyes, yet rarely is his hair color even mentioned, which is possibly so he doesn't outshine his wife in the looks department.

Wicked Stepmother

Youngest Child Wins: The bride is the youngest child in a very large and poor family.

"Sleeping Beauty" (French: La Belle au bois dormant "The Beauty Sleeping in the Wood") by Charles Perrault, or "Little Briar Rose" (German: Dornroschen) by the Brothers Grimm, is a classic fairy tale which involves a beautiful princess, a sleeping enchantment, and a handsome prince. The version collected by the Brothers Grimm was an orally transmitted version of the originally literary tale published by Charles Perrault in Histoires ou contes du temps pass in 1697. This in turn was based on Sun, Moon, and Talia by Italian poet Giambattista Basile (published posthumously in 1634), which was in turn based on one or more folk tales. The earliest known version of the story is found in the narrative Perceforest, composed between 1330 and 1344 and first printed in 1528.

~Source: Wikipedia~

_______________________________________________________________