| ||||

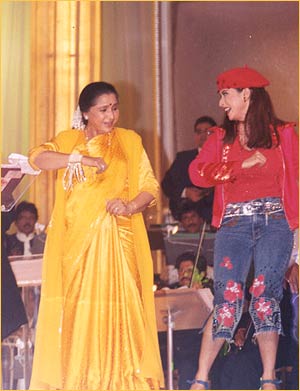

Filmi is a modern-day alchemist's stone, a panacea capable of turning box-office slow death into singing, ringing tills. Ashaji – the ji suffix denotes respect – has been at the top of the Bollywood pantheon of playback legends since the late 1950s. Playback singers are the vocalists who cut the songs to which actors lip-synch. She and her profession have made the soundtrack to untold billions of people's lives. Filmi has remained as a constant in people's lives – Ashaji's is a continent-crossing cultural success story. Yet, despite the scale and trappings of her success, the invitations to film premieres, the self-named restaurant chain in the making ('Asha's') and all the rest, she remains utterly down to earth. Her story weaves together many of the multicoloured strands in the subcontinent's variegated cultural tapestry. Her career has not only seen many changes, it has also contributed to some of the great movements in Indian popular culture.

Before we get too far, a little context may help. Filmi is a visionary creation. It combines pragmatism, multiculturalism and imagination. 'Pictures', as movies were known in the language of the Empire, first arrived in the subcontinent in 1896. During the next few decades, silent film became the ascendant form of popular entertainment. Pictures coined in the annas – and annas made rupees made fortunes. Everything changed in March 1931 when Imperial Films released the Parsee filmmaker Ardeshir M. Irani's Alam Ara. Irani was helped by Wilford Deming, a sound technician from Hollywood, California. Sound rushed in and, where one 'silent language' had done for all, a babble of mutually incomprehensible tongues looked set to alienate the anna-rich millions. (The 1945 edition of the Hindustan Year Book estimated 225 official languages current in India but that left out so-called 'insignificant languages'.) Irani fell back on what pleased crowds: song and dance. For once proving the clichmongers right, music was the universal language. A new formula arose. Songs created a narrative style unique to the Indian subcontinent going into over ninety-nine per cent of Indian commercial films (the film historian Firoze Rangoonwalla found two made between 1931 and 1954 with no songs whatsoever) turning every one into something like a Western musical. In January 1933, HMV (India) – the forerunner of today's Saregama – presciently identified 'the key to prosperity…in the immediate future' to lie in 'Indian Talkie records and Radio Gramophones'. That September, a child called Hope, or in full Asha Dinanath Mangeshkar, was born in Sngali, Maharashtra. Her father, Dinanath Mangeshkar (1901–1942) was a respected actor-singer and exponent of Sangeet Natak, a Marathi regional musical-theatrical tradition. Coincidentally, Sangeet Natak had been heavily influenced by Parsee musical drama which had sharp-focussed Irani's vision. 'Coincidentally', both forms sprinkled popular and semi-classical song interludes through the narrative. Can one choose one's birth? Ashaji was born into what proved to be the century's most influential and successful musical dynasty. Dinanath Mangeshkar's five children – conveniently born every other year on the Western calendar between 1929 and 1937 – all went into the music business. The eldest, Lata Mangeshkar, went on to become Bollywood's most famous playback singer of either sex. The next, Meena became best known as a music director (composer). Asha was the middle child. Usha became a playback singer too, while Dinanath Mangeshkar's only son, Hridaynath, became a music director. After Dinanath's unexpected death in 1942, his wife Shrimati moved from Pune to Kolhapur before settling in Bombay, the booming centre of the wartime Hindi-language film industry, in 1944. Ashaji's son, Anand grins knowingly as he says all five siblings are a strong-willed bunch. Ashaji grew up in an era when cinema was the paramount form of popular entertainment. Traditional forms of entertainment wilted like etiolated specimens in its shadow. Through family string-pulling, she got a cameo in a Marathi-language picture as a child actress. At the age of 10, she disliked the acting but loved the singing. She had found her metier. (Shameless little actress that she is, this lifelong cineaste is prepared to review her position immediately when Jackie Chan offers her a part in one of his films.) By the late 1940s, she was singing in Bombay productions. Success had bred conservatism in the Bombay film industry. Post-Partition, everyone was jockeying for position and consequently her career climb took time. The top songs went to the same clique of playback singers. Ashaji took the recognised – indeed the only – path. She began by sharing a microphone with established vocalists such as Geeta Roy (later Geeta Dutt) and the great Zohrabai, the singer who probably best exemplifies the transition from the old to the new order in popular music. A shared microphone could lead to better things. When Geetaji could not do the right laugh to order in one song, Ashaji stood cued beside her at the microphone. (For a flavour, cue laughter in 'Jawani Jan-E-Man' and 'Sapna Mera Toot Gaya'.) A mother-tongue Marathi speaker, she took on jobs singing in Punjabi, Bengali and (especially) Hindi, earning respect for her reliability, her ear and her innate gift for mimicry. Ashaji's success was hard-won. For years, she took what she could get. The pressure was on and relentless. Day in, day out, she raced from practice session to run-through to recording soundstage. Candidly, she describes much of what she got as 'second-artist songs'. As Lataji's success blotted out others' hopes, a little sibling rivalry piqued her resolve and ambitiousness. She cannot remember all she did during those years on the studio treadmill, but the mere title of a song that meant something can prompt a hummed melody, a passage or a key couplet. Whereas Lataji went from classical through to romantic songs, Ashaji went from classical through romantic songs to pure pop. 'It was the challenge and I like challenges,' she explains. Ashaji was headstrong and ambitious enough to take on risky, sometimes risqu jobs. What really stamped her career was taking on songs that were difficult to sing. 'Sapna Mera Toot Gaya' and 'Mera Naam Hai Shabnam' fall into that category. Though it took until the second half of the 1950s, her perseverance paid off. Her name was on a nation's lips. Looking back from the vantage point of an era of rap and hip-hop, she giggles sly-eyed and unrepentantly about how fast 'Ina Mina Dika' sounded back then. 'Ina Mina Dika' was rock'n'roll scandal Indian-style in 1956, at a time when fast had two popular meanings, and it had a catchy tune. What made Asha Bhosle a household name was her vocal versatility. She was a vocal actress, equally capable of capturing the vocal character of the heroine, the courtesan, the ingnue, the brazen hussy ('Hi, Prince!'), the world-weary woman, the vamp. Some of the 'roles' that she took on were considered strong meat and they enabled her to demonstrate a daring, sometimes controversial side. 'We had to improvise, we had to see what was in the song,' she recalls. What she read into the part determined how the actress acted before the camera and if she knew which actress she was singing for she tried to tailor her performance to that actress's style. The actress Helen would phone to find out when the session was taking place. She made a habit of attending Ashaji's sessions, the better to appreciate the emotional range of the interpretation. The deeper the singer got into the song, the greater potential it gave the actress. She remembers Helen egging her to add more emotion because every extra vocal gesture or nuance enabled the actress to blossom on the silver screen. Using 'Karle Pyar Karle' as an example, she sums the process up: 'Because the song is recorded first, first we act, then she can act.' Western popular music has had a few great recording acts to rival Asha Bhosle. Abba, the Beatles, Frank Sinatra, Madonna and Elvis Presley all supposedly shifted a fair few units. When it comes to matching Asha Bhosle's unit-shifting ability however, it is helpful to think in permutations of a couple of those names. Agreed, it is impossible to state how many millions of units she has shifted (ignoring how much has been pirated). True, her sales have never been subjected to the sort of meticulous scrutiny and audit that people fondly believe occurs as a matter of course in the West. (Perhaps the most innocent example of that concerns the Beatles: Parlophone lost count of how many copies of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band it shipped, such was the rush to meet demand in the months after its release.) What is now beyond dispute is Ashaji's Olympian place as the most recorded artist in history with more than 20,000 documented songs in over a dozen languages. She put down most in one take. Over the decades, much has been made of family frictions in the popular press. Less has been made of how the family has pulled together. Ashaji has shown herself to be a true fighter, a quality that she shares with her big sister. When the standard Indian practice was to take a one-off fee for a song, Lataji, although threatened with all manner of censure, studio lockout and career ruin, fought for a better, more equitable deal, much to the chagrin of many in her profession who did not want the boat rocked. Ashaji fought through the courts for family royalties, winning another lawsuit this year in India. The hope here is to part the veil and reveal a glimpse beyond Bollywood. Hence the inclusion of 'Jaane Kya Haal Ho Kai' and 'Neeyat-E-Shauq'. Each evinces a remarkable maturity and depth as an interpreter. Arguably, in the history of recorded music, only the pan-Arabic singer Umm Kalthm, Lata Mangeshkar, the Beatles and Elvis Presley compare in terms of global cultural impact and influence. However, best of all, Ashaji has more of the great voices (plural) of all time than any vocalist of our age. Try to prove me wrong… |