Sravani, the sacred thread changing ceremony, and Raksha Bandhan are celebrated on the full moon day of the month of Shravan (June-July) and are often regarded as two names for the same festival. This is not strictly true because Sravani is a specifically Brahmin festival referred to in the sacred Sanskrit texts as Rishi Tarpan or Upa Karma. It is a very ancient Vedic festival and even today is regarded as important in Bengal, Orissa, southern India, Gujarat and some other states.

The more popular of the two festivals, however, is Raksha Bandhan.We do not have any reliable evidence on when, why or where Raksha Bandhan came into vogue. There is, however, a well-known tale in the Puranas about a fierce battle that raged between the gods and demons. From news received from the battlefield it appeared that the demons were getting the upper hand and would gain victory.

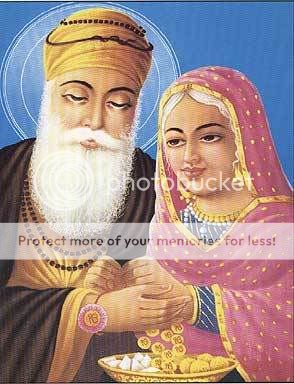

Bebe Nanaki sister of Guru Nanak tying rakhri to her brother

Indra, the supreme deity, summoned his teacher Vrihaspati to his court for advice. Indra's wife Indrani was also present. Before the teacher could speak, Indrani rose and said, "I know how to assure the victory of the gods. I give you my word that we will win."

The next day was the full moon night of the month of Shravan. Indrani had a charm prepared as prescribed by the sacred texts and tied it on the wrist of her husband. And no sooner did Indra appear on the battlefield with the charm onhis hand than the demons scattered and fled. The demons bit the dust and the gods were victorious.

It would appear that the Raksha Bandhan of today is derived from this belief. It is held that if a chord made according to the prescriptions of the holy texts is tied round the wrist of a person on the full moon day of Shravan it will ensure him good health, success and happiness for the year that follows.

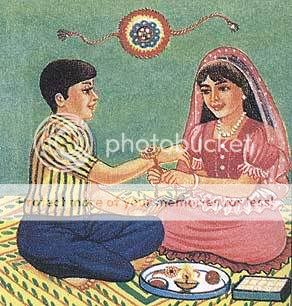

Whatever be the origin of Raksha Bandhan, today it has come to be a kind of sisters' day, symbolising the love that binds them to their brothers.No matter where a brother may be, be he across the seven seas, on this day he must wear the coloured chord round his wrist. You can realise the sanctity of this custom from the fact that, even if a girl who is a total stranger ties this chord on the wrist of a young man, from then on the two regard each other as brother and sister and consider themselves closer than other blood relations.

Many days before the festival, stalls are set up at different places, packed with colourful and glittering masses of Raksha Bandhan wristlets. In some smaller towns, whole rows of bazaars sell nothing but these rakhis of all shapes and hues—red, yellow, pink, green, blue, trimmed with silver and gold thread. At these stalls one can see throngs of women of all ages, ranging from tiny tots to middle-aged matrons, who come for their rakhi shopping dressed in their best fineries, as colourful as the rakhis they buy. Rakhi prices vary from five paise for a coloured string to a gaudy silver-and-gold laced affair worth five rupees.

At the same time, sweetmeat vendors do a roaring trade. They put out all their delicacies on display—laddoos, jalebis, barfi, balushahi, imarti, gulab jamuns, rasgullas and cham-cham—the more you gaze at them, the more yourmouth will water. You forget all the doctor's warnings that eating sweets is bad for the teeth and digestion; these sweets are a must for Raksha Bandhan.

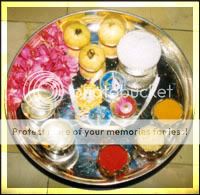

When the great day dawns (the full moon night of July-August), the girls' excitement has to be seen to be believed. On other days they may sleep late but on Raksha Bandhan they are up before dawn. After a quick bath, they get into their best clothes. By then their brothers are also bathed and dressed. Then the girls take the rakhi still attached to its strip of cardboard and put it on top of a thali full of sweets. Covering her head with her dupatta, the sister seats herself in front of her brother, daubs his forehead with vermillion, saffron and rice powder, takes the colourful rakhi and ties it to his wrist. She will then take a piece of some sweetmeat and playfully stuff it in her brother's mouth. He, in his turn, as a mark of his affection, places some money on the thali—it may be anything upward of a rupee. Till the girls have tied the chord on their brothers' wrists neither will break their fast. All that day, till the evening, the brother will keep the rakhi on his wrist. It is also customary to fry poories and cook vermicelli pudding on this occasion.