Kanailal and Brother, Calcutta:

The History of an Indian Musical Instrument Maker

|

|

By Steven Landsberg, Santa Fe NM, Calcutta, India

At about the same time that the last Mogul Emperor Bahadur Shah II was to witness his final days on the throne, a Bengali named Damodar Adhikari was born into a family of brahmin priests in Calcutta. Although these two events have no significant connection, the end of the Mogul Empire and the stabilization of British rule and discipline, interfaced with a Bengali renaissance, brought about conditions favorable to a thriving and enthusiastic artistic environment. It was during this time that Damodar Adhikari grew up; and although music was not part of his family heritage, it was not unusual that he took an interest in both sitar and surbahar. Although he never became well known for his musicianship, his engagement in the musical arts led him to investigate the manufacturing of the popular instruments of his time; namely, sitar, surbahar, and veena. In 1882 he established a workshop with the assistance of three or four other instrument makers. As he had no knowledge of instrument making at this time, he took the assistance of one Natabar Lal Das, son of Anantalal Das, one of the best instrument makers of the time.After gaining much experience under the tutelage of Natabar, Damodar became a competent instrument maker. Under the name Damodar and Sons, the shop turned out numerous sitars and esrajes (a fretted stringed instrument played with a bow.) How many veenas and surbahars they made is uncertain; but they knew and followed the tradition of veena making, which required not only skilled craftsmanship but also the recitation of mantra and the proper performance of certain offerings as each part of the instrument was made. Natabar knew what to do, and Damodar, a priest by caste, was able to do it.

Although Damodar laid the foundation for a successful business, it never achieved high acclaim. In fact there were other shops at that time that were better established. That trend was to change after Damodar's premature death in 1905.

Damodar left two sons behind. The eldest was Kannailal and the other was Nityananda. They were still teenagers when their father died and had not had enough experience to oversee the manufacturing process. Fortunately, Natabar Lal agreed to remain with the firm and train the two boys as his apprentices in the fine art of making sitar, surbahar, esraj, and veena. At about the same time two other important figures manifested to help the boys continue their apprenticeship. These two men had been friends of Damodar and every evening they would come to the shop for some informal talk. Remarking the eagerness of Nityananda to learn all the aspects of instrument making, they took up the task of training him in their respective arts. Amulya Bhaskar, one of the finest carvers of the time, taught Nityananda his craft; and Puraschandra Sen, a fine commercial artist, taught him drawing and engraving. As the two brothers developed their skills, the shop gained in popularity. Musicians began to congregate there and engage in traditional Bengali gossip sessions that had as their primary focus music and musical instruments. When Natabar died around 1910, the name of the shop changed to Kannailal and Brother. Although the shop was named after the elder brother, it seems that the younger Nityananda was the artist and innovator in the family. The shop of Kanailal and Brother was located in a cultural oasis, known as the Barabazar area of Calcutta. Both the renowned poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore and the maharaja Sourendra Mohan Tagore, a great patron of the arts, lived in the same area. Many musicians, poets, and writers inhabited this cultural belt of early twentieth century Calcutta and gave it the aesthetic color and feeling that is to this day an inspiration for many of Bengal's contemporary artists. Although today that artistic flavor has been replaced by the sounds of old buses, trucks, and taxi cabs, one can still find many music and stone sculpture shops in the Barabazaar area. Kanailal died a premature death sometime in the 1930's leaving his brother Nityananda to maintain and develop the instrument business. A skillful craftsman Nityananda not only raised the level of instrument making and carving to a very fine art but also invented some tools for engraving and for wood boring the long neck of the rudra veena. Nityananda's influence on the production of the modern sitar cannot be overestimated. From the

Damodar left two sons behind. The eldest was Kannailal and the other was Nityananda. They were still teenagers when their father died and had not had enough experience to oversee the manufacturing process. Fortunately, Natabar Lal agreed to remain with the firm and train the two boys as his apprentices in the fine art of making sitar, surbahar, esraj, and veena. At about the same time two other important figures manifested to help the boys continue their apprenticeship. These two men had been friends of Damodar and every evening they would come to the shop for some informal talk. Remarking the eagerness of Nityananda to learn all the aspects of instrument making, they took up the task of training him in their respective arts. Amulya Bhaskar, one of the finest carvers of the time, taught Nityananda his craft; and Puraschandra Sen, a fine commercial artist, taught him drawing and engraving. As the two brothers developed their skills, the shop gained in popularity. Musicians began to congregate there and engage in traditional Bengali gossip sessions that had as their primary focus music and musical instruments. When Natabar died around 1910, the name of the shop changed to Kannailal and Brother. Although the shop was named after the elder brother, it seems that the younger Nityananda was the artist and innovator in the family. The shop of Kanailal and Brother was located in a cultural oasis, known as the Barabazar area of Calcutta. Both the renowned poet-philosopher Rabindranath Tagore and the maharaja Sourendra Mohan Tagore, a great patron of the arts, lived in the same area. Many musicians, poets, and writers inhabited this cultural belt of early twentieth century Calcutta and gave it the aesthetic color and feeling that is to this day an inspiration for many of Bengal's contemporary artists. Although today that artistic flavor has been replaced by the sounds of old buses, trucks, and taxi cabs, one can still find many music and stone sculpture shops in the Barabazaar area. Kanailal died a premature death sometime in the 1930's leaving his brother Nityananda to maintain and develop the instrument business. A skillful craftsman Nityananda not only raised the level of instrument making and carving to a very fine art but also invented some tools for engraving and for wood boring the long neck of the rudra veena. Nityananda's influence on the production of the modern sitar cannot be overestimated. From the early days of his instrument-making career, he was setting the standard for sitars. Instruments made before the twentieth century were not heavily engraved with designs on celluloid. Fine woodcarving was also not a trademark of older sitars. Nityananda took a keen interest in both engraving and woodcarving and incorporated these two skills into his instrument making. He later developed a tool for engraving on celluoid. Nityananda's influence on this aspect of instrument manufacturing was so strong that eventually all the other manufacturers of instruments eventually copied this trend. Nityananda rounded the edges of the frets. Until that time the frets, although curved across the neck of the sitar, had a flat edge with tracks on either side that provided support for binding the fret to the sitar. Called Ganga -Yamuna frets, they were so named because of the two parallel tracks bordering the main body of the fret. Nityanada discovered that the rounded fret gave a finer tone and were also easier to tie. He made the neck of the instrument into a concave curve. The necks prior to that time were squarer than they are today; and as a result, the instrument was more difficult to handle. He standardized the measurements of the instrument and refined the proportions of all its parts so that one could pull the wire over a span of five notes from one fret. Nityananda adjusted the thickness of the neck, the size of the bridge, and the thickness of its legs. He proportioned the height of the ara (the bone piece which holds the strings in place on the pegbox side). He adjusted the scale length so that the bass note and the highest note would have a similar tonal quality. This is

early days of his instrument-making career, he was setting the standard for sitars. Instruments made before the twentieth century were not heavily engraved with designs on celluloid. Fine woodcarving was also not a trademark of older sitars. Nityananda took a keen interest in both engraving and woodcarving and incorporated these two skills into his instrument making. He later developed a tool for engraving on celluoid. Nityananda's influence on this aspect of instrument manufacturing was so strong that eventually all the other manufacturers of instruments eventually copied this trend. Nityananda rounded the edges of the frets. Until that time the frets, although curved across the neck of the sitar, had a flat edge with tracks on either side that provided support for binding the fret to the sitar. Called Ganga -Yamuna frets, they were so named because of the two parallel tracks bordering the main body of the fret. Nityanada discovered that the rounded fret gave a finer tone and were also easier to tie. He made the neck of the instrument into a concave curve. The necks prior to that time were squarer than they are today; and as a result, the instrument was more difficult to handle. He standardized the measurements of the instrument and refined the proportions of all its parts so that one could pull the wire over a span of five notes from one fret. Nityananda adjusted the thickness of the neck, the size of the bridge, and the thickness of its legs. He proportioned the height of the ara (the bone piece which holds the strings in place on the pegbox side). He adjusted the scale length so that the bass note and the highest note would have a similar tonal quality. This is  very difficult on an instrument with such a long fret board. He fixed the method by which the neck is attached to the gourd so that the playing wire falls in the middle of the instrument and the bridge sits in the middle of the tabli (the flat wooden cover on top of the gourd). Positioning the bridge in this away allows the whole tabli to vibrate evenly. He also made similar adjustments to other instruments such as the veena, esraj and surbahar. In the early twentieth century, some sitar players played on a rather small sitar, mainly at higher tempos. Others from the Jaipur area played on a larger sitar called a sitar-been and concentrated their music into the Maseetkhani baj. Then again, some sitar players who wanted to develop the slower unaccompanied part of the music, required a second instrument called a surbahar, a larger deeper toned instrument, which looks like an oversized sitar, but is more like a rudra veena. Until the 1930's there was hardly a sitar player who could demonstrate equally the two styles of sitar. Some played the faster Rezakhani baj and others played the slower Maseetkhani style. Few

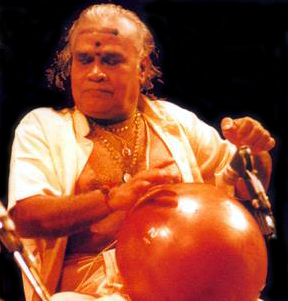

very difficult on an instrument with such a long fret board. He fixed the method by which the neck is attached to the gourd so that the playing wire falls in the middle of the instrument and the bridge sits in the middle of the tabli (the flat wooden cover on top of the gourd). Positioning the bridge in this away allows the whole tabli to vibrate evenly. He also made similar adjustments to other instruments such as the veena, esraj and surbahar. In the early twentieth century, some sitar players played on a rather small sitar, mainly at higher tempos. Others from the Jaipur area played on a larger sitar called a sitar-been and concentrated their music into the Maseetkhani baj. Then again, some sitar players who wanted to develop the slower unaccompanied part of the music, required a second instrument called a surbahar, a larger deeper toned instrument, which looks like an oversized sitar, but is more like a rudra veena. Until the 1930's there was hardly a sitar player who could demonstrate equally the two styles of sitar. Some played the faster Rezakhani baj and others played the slower Maseetkhani style. Few played the unaccompanied portion called alap on the sitar. With the methods that Nityananda found for adjusting the proportion of the sitar, players could now handily play all the aspects of Indian music on one instrument. Artists nowadays give equal attention to alap, Maseetkhani and Rezakhani. The small sitar disappeared and although the surbahar is still around, it lost the popularity that it had during the last part of the nineteenth century. Nowadays, however, there seems to be a resurging fascination with the surbahar. Other craftsmen trained in the Kanailal and Brother shop. Although they would generally be involved with the tedious aspects of instrument making, such as the production of frets and pegs; their exposure to Nityananda's fine work gave them the opportunity to observe and learn. These craftsmen, after leaving the Kanailal shop, would then go and work for other instrument manufacturers in Calcutta. As they had witnessed the work of Nityananda and his brother, they would try to reproduce the same sitar, particularly the more visible aspects. In this way the sitar became more and more standardized throughout Calcutta. These craftsmen never received the full training, especially in regard to the refined inner qualities of the instrument. Albeit impossible for them to reproduce the sitar that was stamped with the name of Kanailal and Brother, they still introduced many of Nityananda's innovations into the general marketplace. The trademark of the Kanailal sitar was its fine tone. If words could describe tone, then one might say that it had a sound whose texture contained evenly layered overtones as fine as smooth sand, no grain larger than another. The result was a note that had a precise center with a radiating periphery that imbibes each slide and glissando with a proportioned granulation. The Kanailal sitar became so popular that it was highly demanded throughout India from the 1920s to the 1960's. Every great sitar player of that period including Enayet Khan, Waheed Khan, Mushtaq Ali Khan, Vilayat Khan, and Ravi Shankar knew the 'Kanailal and Brother' shop on Upper Chittpur Road and owned one of their instruments. Nityananda also made sarods for the great sarodiyas of the time including Keramatullah Khan, Kukubh Khan, Amir Khan, Radhika Mohan Moitra, and Shyam Ganguli. He also made instruments for the maharaja Sourendra Mohan Tagore. During his lifetime Nityananda made about four veenas according to the instructions he had received from Natabar Lal. Nityanada retired in l960 leaving the shop to his son Murari and nephew Govinda. He expired on October 22, 1972.

played the unaccompanied portion called alap on the sitar. With the methods that Nityananda found for adjusting the proportion of the sitar, players could now handily play all the aspects of Indian music on one instrument. Artists nowadays give equal attention to alap, Maseetkhani and Rezakhani. The small sitar disappeared and although the surbahar is still around, it lost the popularity that it had during the last part of the nineteenth century. Nowadays, however, there seems to be a resurging fascination with the surbahar. Other craftsmen trained in the Kanailal and Brother shop. Although they would generally be involved with the tedious aspects of instrument making, such as the production of frets and pegs; their exposure to Nityananda's fine work gave them the opportunity to observe and learn. These craftsmen, after leaving the Kanailal shop, would then go and work for other instrument manufacturers in Calcutta. As they had witnessed the work of Nityananda and his brother, they would try to reproduce the same sitar, particularly the more visible aspects. In this way the sitar became more and more standardized throughout Calcutta. These craftsmen never received the full training, especially in regard to the refined inner qualities of the instrument. Albeit impossible for them to reproduce the sitar that was stamped with the name of Kanailal and Brother, they still introduced many of Nityananda's innovations into the general marketplace. The trademark of the Kanailal sitar was its fine tone. If words could describe tone, then one might say that it had a sound whose texture contained evenly layered overtones as fine as smooth sand, no grain larger than another. The result was a note that had a precise center with a radiating periphery that imbibes each slide and glissando with a proportioned granulation. The Kanailal sitar became so popular that it was highly demanded throughout India from the 1920s to the 1960's. Every great sitar player of that period including Enayet Khan, Waheed Khan, Mushtaq Ali Khan, Vilayat Khan, and Ravi Shankar knew the 'Kanailal and Brother' shop on Upper Chittpur Road and owned one of their instruments. Nityananda also made sarods for the great sarodiyas of the time including Keramatullah Khan, Kukubh Khan, Amir Khan, Radhika Mohan Moitra, and Shyam Ganguli. He also made instruments for the maharaja Sourendra Mohan Tagore. During his lifetime Nityananda made about four veenas according to the instructions he had received from Natabar Lal. Nityanada retired in l960 leaving the shop to his son Murari and nephew Govinda. He expired on October 22, 1972.  Murari and Govinda continued to make instruments according to the tradition established by their fathers and grandfather. In fact, one may find one of their sitars, surbahars, and veenas, in practically every part of the world today. Murari Adhikari made instruments for Ziamoinuddin Dagar, Asat Ali Khan, Imrat Khan, and Ravi Shankar (sitar and surbahar). Murari made his first veena for Ziamoinuddin Dagar in l960. Ziamonuddin made frequent visits to the shop on numerous occasions and demonstrated vocally the type of sound that he wanted. Murari did the research and made the necessary adjustments to make the instrument produce the sound Ziamoinuddin wanted. Ziamoinuddin was quite please with that veena and as a result Murari had the opportunity to make veenas for many of his students. Murari introduced some changes in the manufacturing of the veena just as his father had done for the sitar. He made about 50 veenas during his professional career and they are presently in the hands of players all over the world.

Murari and Govinda continued to make instruments according to the tradition established by their fathers and grandfather. In fact, one may find one of their sitars, surbahars, and veenas, in practically every part of the world today. Murari Adhikari made instruments for Ziamoinuddin Dagar, Asat Ali Khan, Imrat Khan, and Ravi Shankar (sitar and surbahar). Murari made his first veena for Ziamoinuddin Dagar in l960. Ziamonuddin made frequent visits to the shop on numerous occasions and demonstrated vocally the type of sound that he wanted. Murari did the research and made the necessary adjustments to make the instrument produce the sound Ziamoinuddin wanted. Ziamoinuddin was quite please with that veena and as a result Murari had the opportunity to make veenas for many of his students. Murari introduced some changes in the manufacturing of the veena just as his father had done for the sitar. He made about 50 veenas during his professional career and they are presently in the hands of players all over the world.

As trends in musical taste changed dramatically after independence in 1947, the name of Kanailal and Brother became more associated with the traditional sitar. Modern artists after the 1950's began looking for a 'modern' sound that was blunter, louder, and without overtones. The traditional sitar with its rich array of overtones was difficult to control when amplified through the microphone and new artists found the 'dryer' sound to be more appealing when it was interfaced with amplification. These changes were to gradually have their toll on the Kanailal tradition. Neither Murari nor his brother wanted to change their family tradition to suit the market. Although they did make sitars according to market demand, they were never satisfied. Eventually, the market buyers turned against them and chose other manufacturers in their place. The shop was permanently closed in 1995 and thus a tradition spanning three generations and over one century came to an end. Although Murari continues to make sitar and veena on a private basis, it will not be long before the making of traditional Indian instruments such as surbahar, and veena will be lost. Unfortunately, the "Kanailal tone" will also disappear and it will take years of research before that sound can be recovered. There is a small sitar with kachipa (tortoise shaped) gourd made by Nityananda in his early days of making instruments. In fact he was about 21 when he made this sitar. He always kept it with him and practiced and played on it regularly during his lifetime. It is very simple in appearance, and although this instrument bears the signature of the tonal quality of that period just prior to the creation of the modern sitar, it is not completely representative of his carving and fine engraving abilities. This sitar is presently maintained by Steven Landsberg in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Eventually it will have a permanent home at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Nityananda's son Murari Adhikari made the sitar that is presently being donated to the museum. The body of the sitar is made from Burma teak wood and the pegs are made from ebony. Fully decorated, this sitar reveals the fine woodcarving and engraving techniques that Nityananda originated. The main characteristic of this sitar is its bright tone, which is partly the result of the large hole just in front of the bridge.