| |

EthymologyThe word Naga comes from the Sanskrit (???) , and nag is still the word for snake, especially the cobra, in most of the languages of India. Female Nagas are called Nagis or Naginis. In the East Indian pantheon it is connected with the Serpent Spirit and the Dragon Spirit. When we come upon the word in Buddhist writings, it is not always clear whether the term refers to a cobra, an elephant (perhaps this usage relates to its snake-like trunk, or the pachyderm's association with forest-dwelling peoples of north-eastern India called Nagas,) or even a mysterious person of nobility. It is a term used for unseen beings associated with water and fluid energy, and also with persons having powerful animal-like qualities or conversely, an impressive animal with human qualities. OriginsAccording to legend, Nagas are children of Kadru, the granddaughter of the god Brahma, and her husband, Rishi or sage, Kasyapa, the son of Marichi. Kashyapa is said to have had by his twelve wives, other diverse progeny including reptiles, birds, and all sorts of living beings. They are denizens of the netherworld city called Bhogavati. It is believed that ant-hills mark its entrance. Nagas lived on earth at first, but their numbers became so great that Brahma sent them to live under the sea. They reside in magnificent jeweled palaces and rule as kings at the bottom of rivers and lakes and in the underground realm called Patala. RoleLike humans, Nagas show wisdom and concern for others but also cowardice and injustice. Nagas are immortal and potentially dangerous when they have been mistreated. They are susceptible to mankind's disrespectful actions in relation to the environment. The expression of the Nagas' discontent and agitation can be felt as skin diseases, various calamities and so forth. Additionally, Nagas can bestow various types of wealth, assure fertility of crops and the environment as well as decline these blessings. Nagas also serve as protectors and guardians of treasure—both material riches and spiritual wealth. Stories are given - e.g., in the Bhuridatta Jataka - of Nagas, both male and female, mating with humans; but the offspring of such unions are watery and delicate (J.vi.160). The Nagas are easily angered and passionate, their breath is poisonous, and their glance can be deadly (J.vi.160, 164). They are carnivorous (J.iii.361), their diet consisting chiefly of frogs (J.vi.169), and they sleep, when in the world of men, on ant hills (ibid., 170). The enmity between the Nagas and the Garulas is proverbial (D.ii.258). At first the Garulas did not know how to seize the Nagas, because the latter swallowed large stones so as to be of great weight, but they learnt how in the Pandara Jataka. The Nagas dance when music is played, but it is said (J.vi.191) that they never dance if any Garula is near (through fear) or in the presence of human dancers (through shame). The word Naga comes from the Sanskrit, and nag is still the word for snake, especially the cobra, in most of the languages of India. When we come upon the word in Buddhist writings, it is not always clear whether the term refers to a cobra, an elephant (perhaps this usage relates to its snake-like trunk, or the pachyderm's association with forest-dwelling peoples of north-eastern India called Nagas,) or even a mysterious person of nobility. It is a term used for unseen beings associated with water and fluid energy, and also with persons having powerful animal-like qualities or conversely, an impressive animal with human qualities. Mythology In myths, legends, scripture and folklore, the category naga comprises all kinds of serpentine beings. Under this rubric are snakes, usually of the python kind (despite the fact that naga is usually taken literally to refer to a cobra,) deities of the primal ocean and of mountain springs; also spirits of earth and the realm beneath it, and finally, dragons.

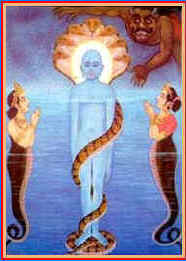

Here we see the king and queen of water nagas worshipping Parshva, the Jain Tirthankara of the era before this one. All nagas are considered the offspring of the Rishi or sage, Kasyapa, the son of Marichi. Kashyapa is said to have had by his twelve wives, other diverse progeny including reptiles, birds, and all sorts of living beings. They are denizens of the netherworld city called Bhogavati. It is believed that ant-hills mark its entrance. The naga-Varuna connection is retained in Tibetan Buddhism, where Varuna, lord of weather, is known as Apalala Nagarajah. As a category of nature spirit:

The bodhisattva Manjushri, in wrathful form, can appear as Nagaraksha (Tib: jam.pal lu'i drag.po). Nagas and WaterWater symbolizes primordial Wisdom and in psychoanalysis, the storehouse that is the unconscious mind. However, to paraphrase Sigmund Freud commenting on the interpretation of symbols in dreams, "Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar." That is, the water in naga lore is really wet. In the language of Kashmir, the word for "a spring" is naga and, in fact, nagas are considered the earliest inhabitants of that region. In a sense this is borne out by geology since that valley was once

Kashmiri names such as Vishnasar and Krishnasar are Vaishnavite ones where the suffix sar means 'reservoir.' Even though Kashmir may be Muslim-dominated in contemporary times, a spring is "understood as naga and enjoys the respect of every religion."

|

In Indian mythology, Nagas are primarily serpent-beings living under the sea. However, Varuna, the Vedic god of storms, is viewed as the King of the Nagas, ie. Nagarajah.

In Indian mythology, Nagas are primarily serpent-beings living under the sea. However, Varuna, the Vedic god of storms, is viewed as the King of the Nagas, ie. Nagarajah.